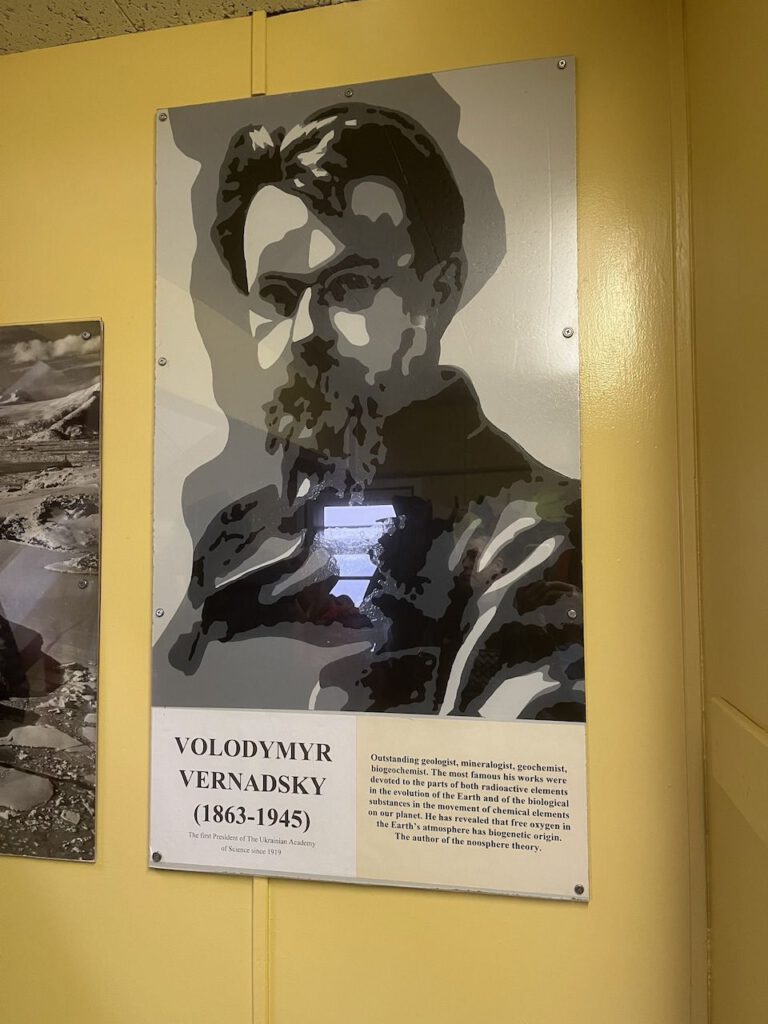

We set off from Vernadsky two days ago. The break did us good, but now we want to continue. For most Antarctic travelers, the southernmost point is reached at the latest here at the Ukrainian Station or even a little to the north after passing through the Lemaire Channel, at Petermann Island, and it’s time to turn back. But not for us. We have the time and inclination to head further south. Adelaide Island is our destination.

Across the Arctic Circle to the south

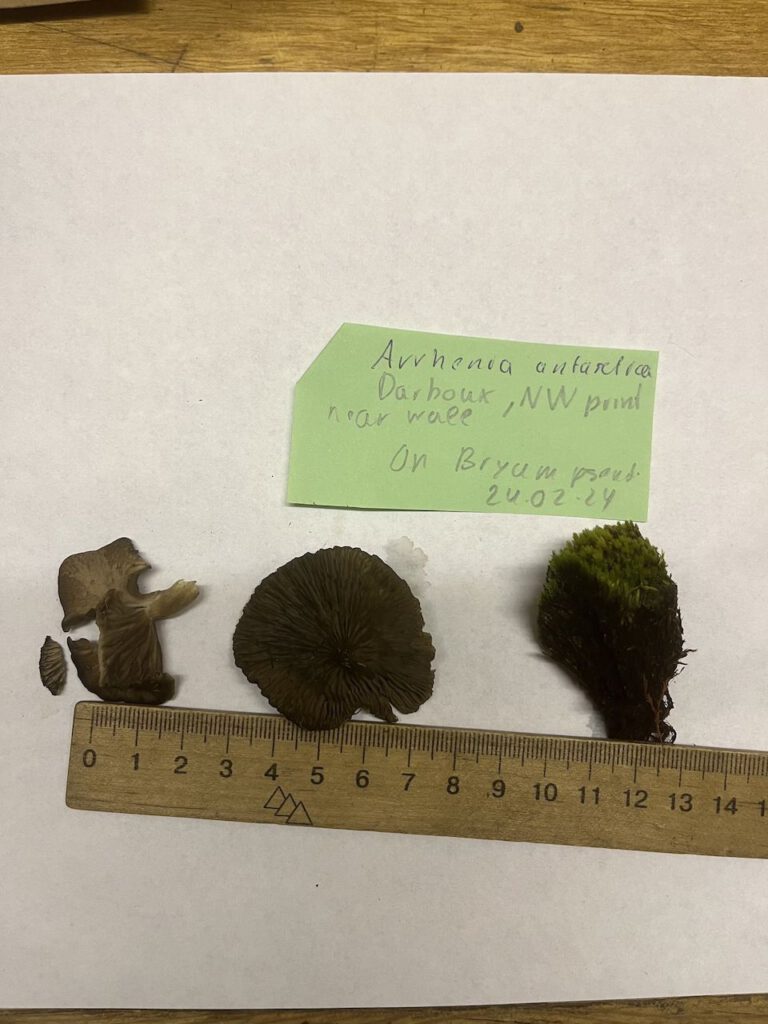

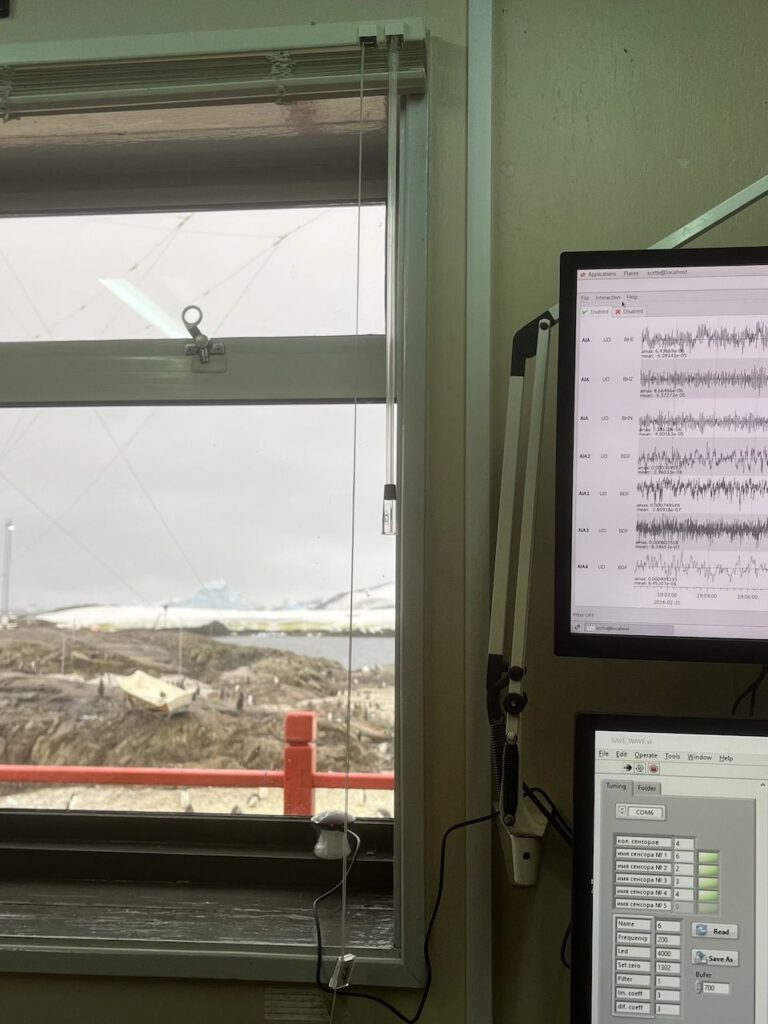

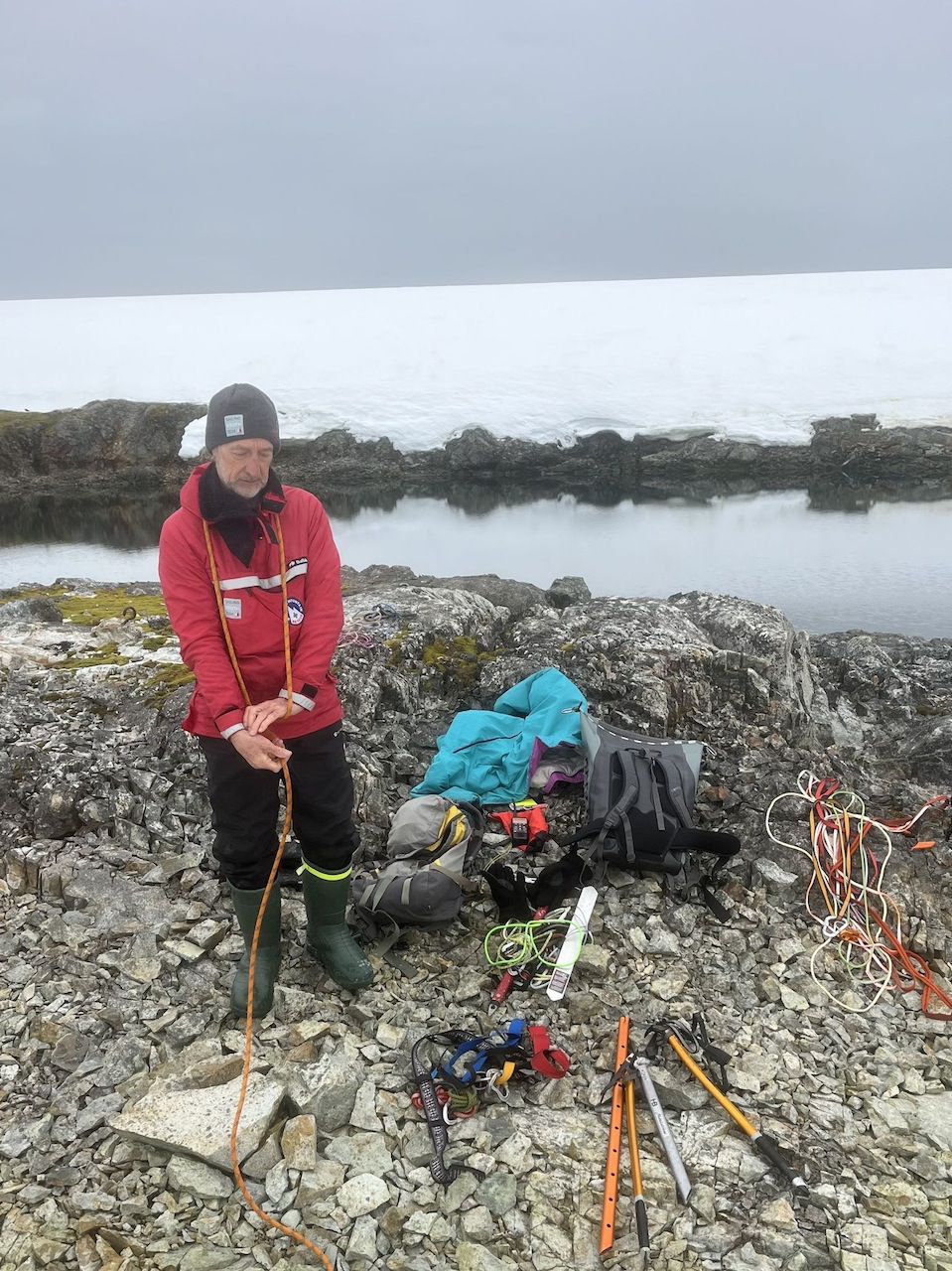

On the one hand, there may be some opportunities for the Mountaineering Team to let off steam on land for a few days. On the other hand, we have taken Ivan on board, a biologist from Vernadsky. And for him, our journey south is a rare and wonderful opportunity to pursue his passion and science – the study of Antarctic plants, especially mosses – and to collect samples at selected locations along the way.

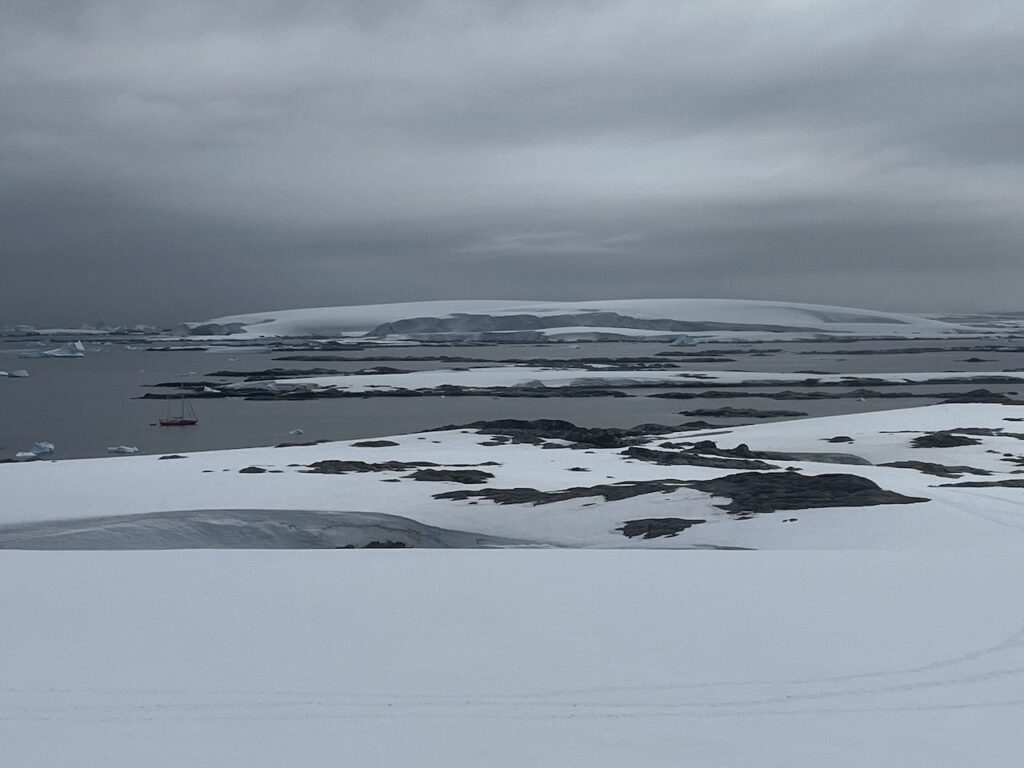

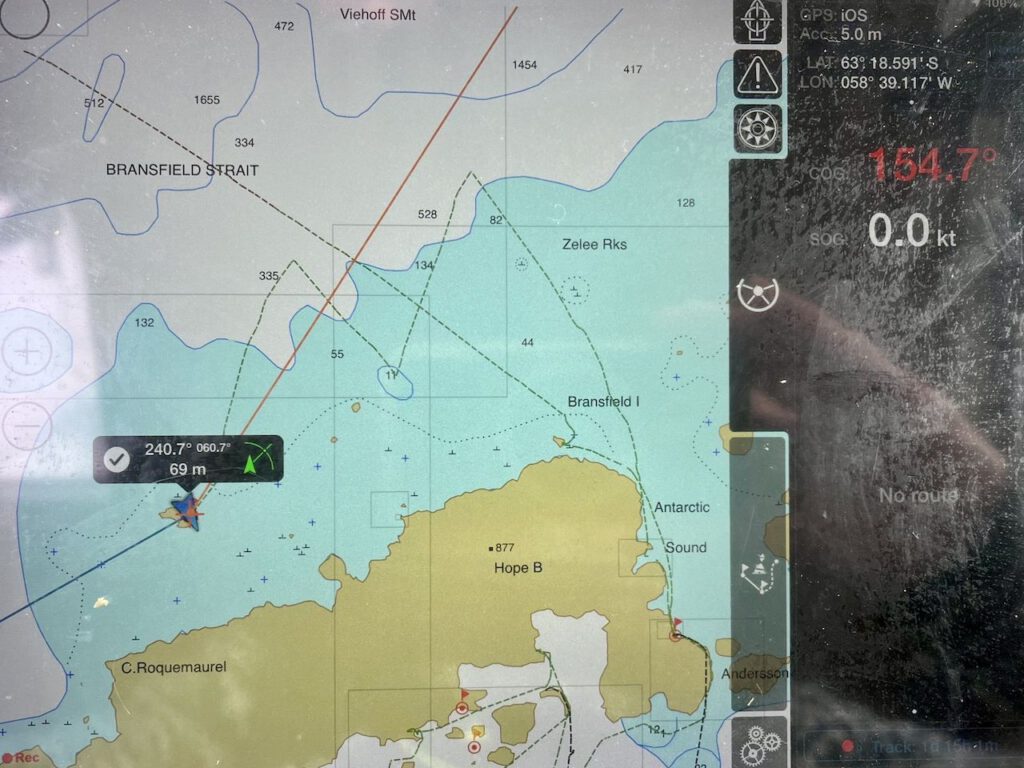

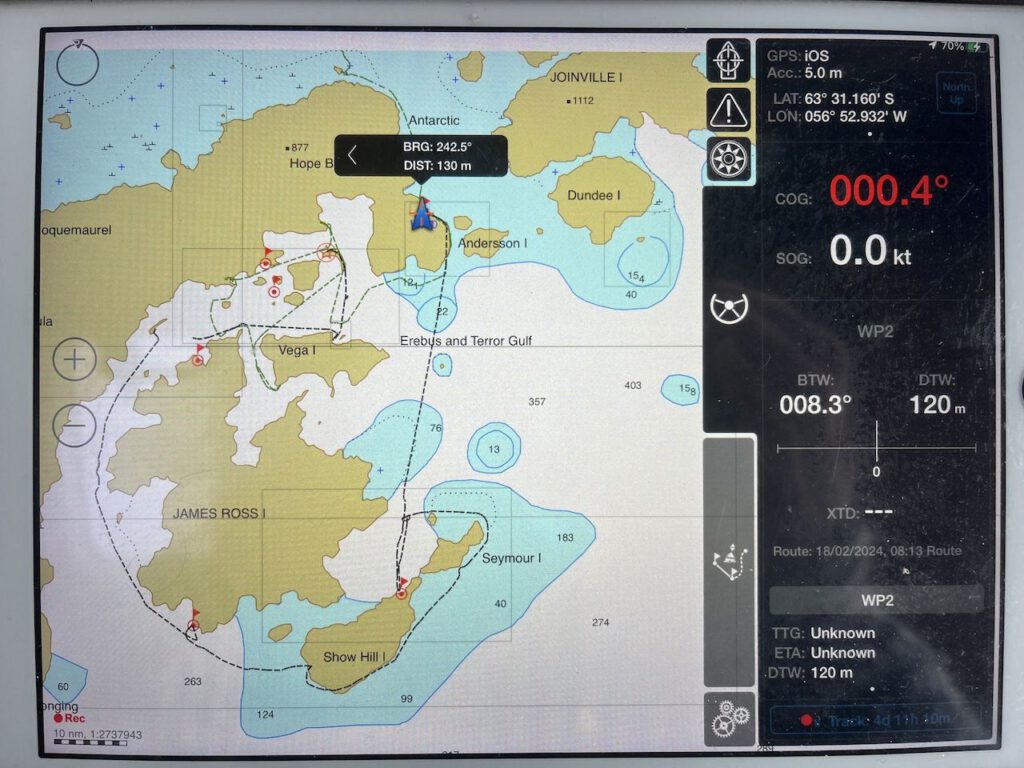

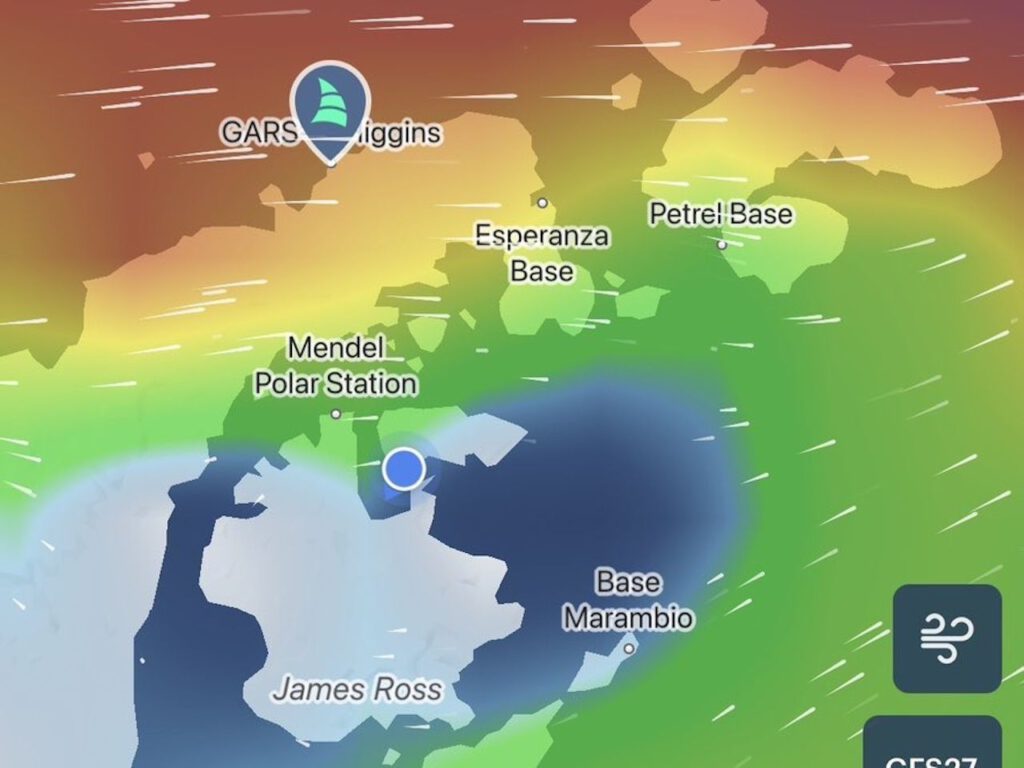

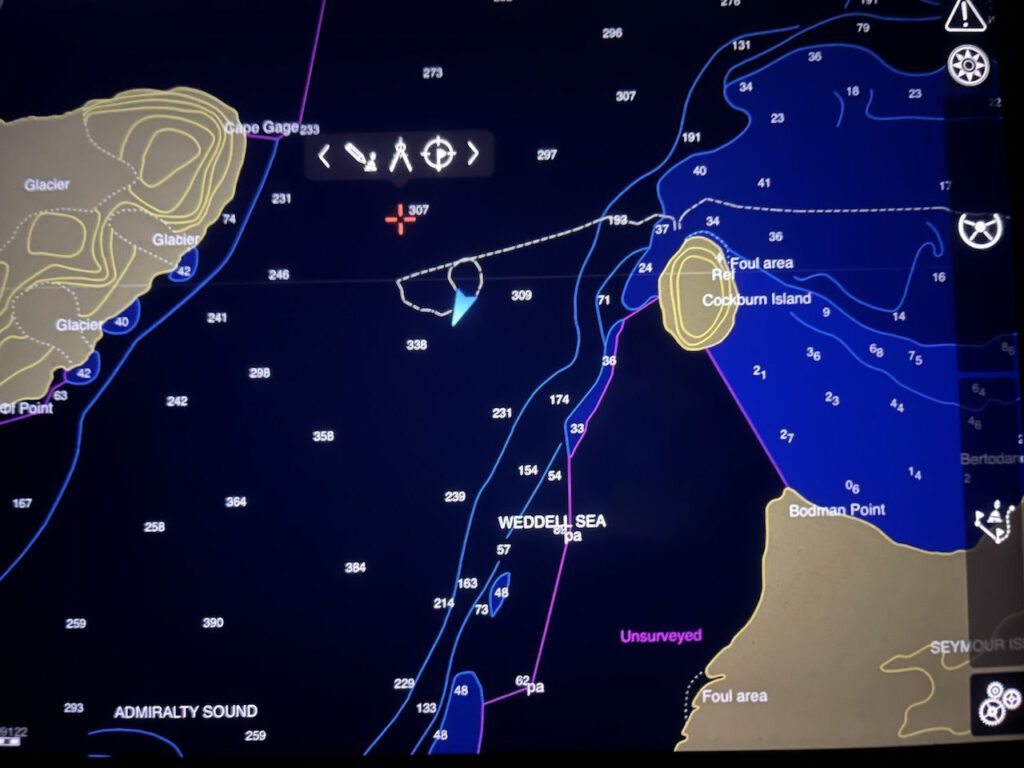

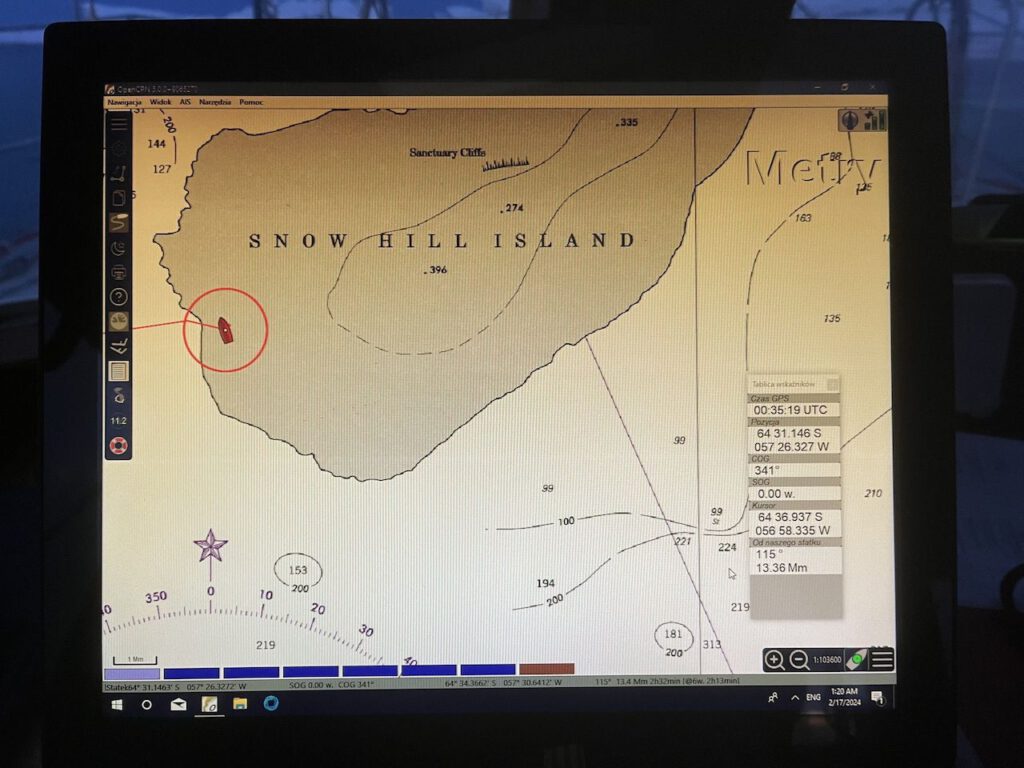

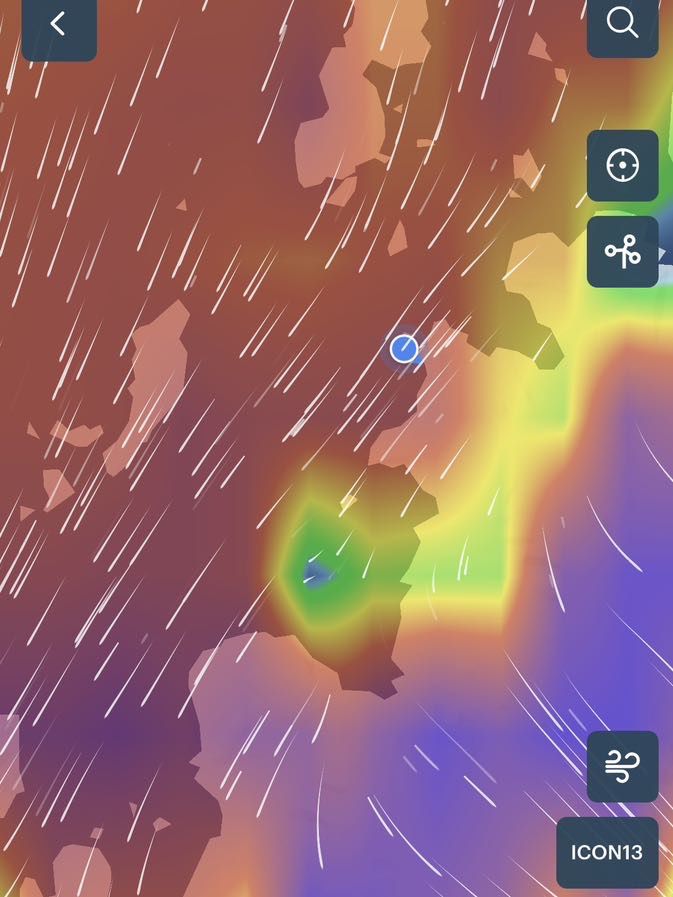

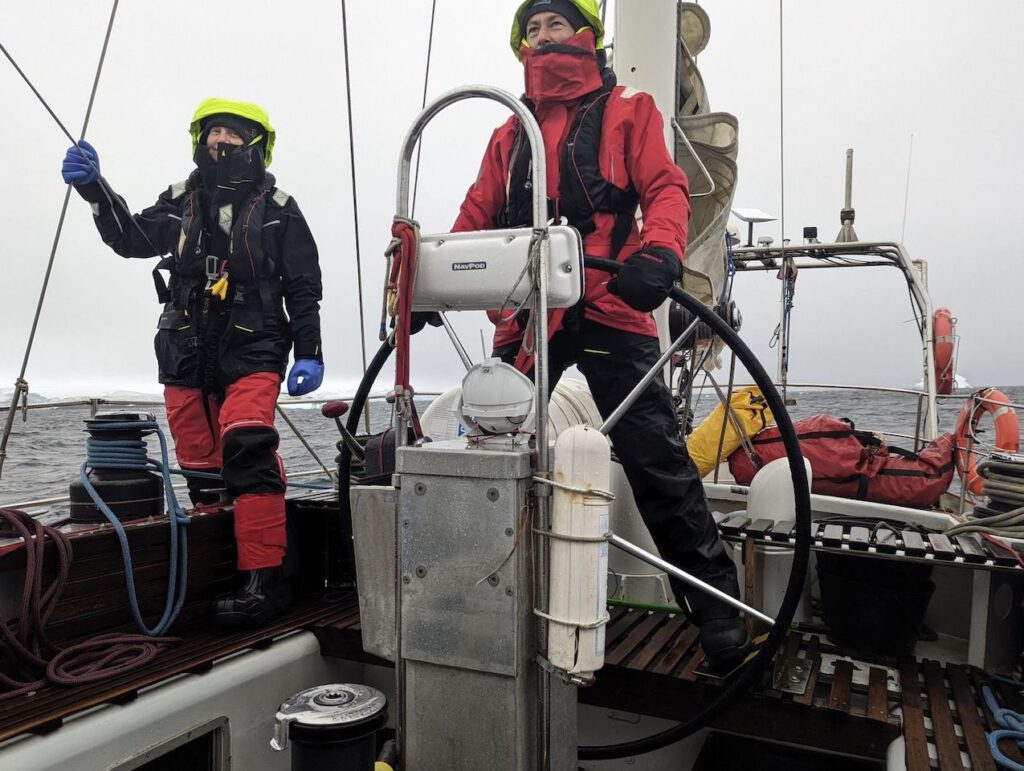

We want to head south as quickly as possible to Marguerite Bay between Adelaide Island and the Peninsula / mainland. The weather is not exactly at its best: it is cloudy, gray and wet. The water – almost black – is dotted with small white whitecaps and numerous icebergs and bergy bits. After four hours, however, you can usually see the smiling faces of those on watch, dripping with wetness. The weather doesn’t make anchoring in the evening easy either: a first attempt at Marie Island fails because the wind is too strong from the wrong direction for the spot, and we have to discard other options because the depth is too great. We sail south for another two hours until we finally drop anchor in a bay near Cape Bellue.

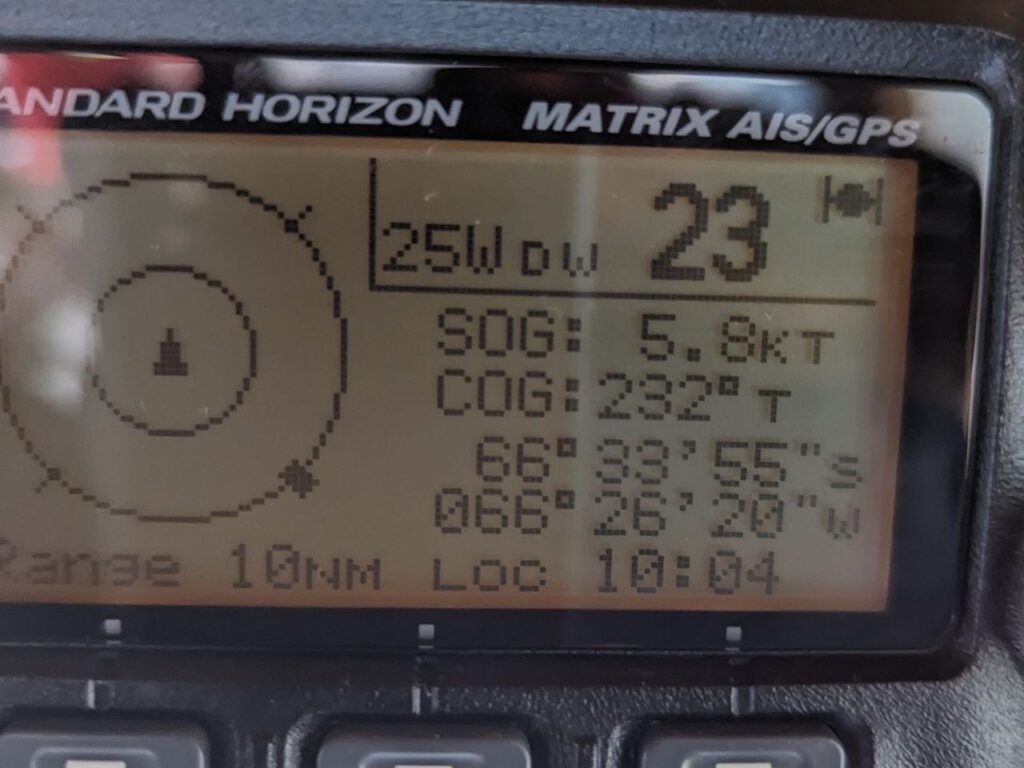

It’s still wet and gray when we cross the Arctic Circle at 66 degrees 33′ 55” at around ten o’clock on Wednesday. A reason to unpack the bottle of rum and clink glasses. It’s never been so crowded in the wheelhouse. My watch has just started, so I have the good fortune and honor of being at the helm during this special event, but I also get a glass in my hand and share my rum with Neptune.

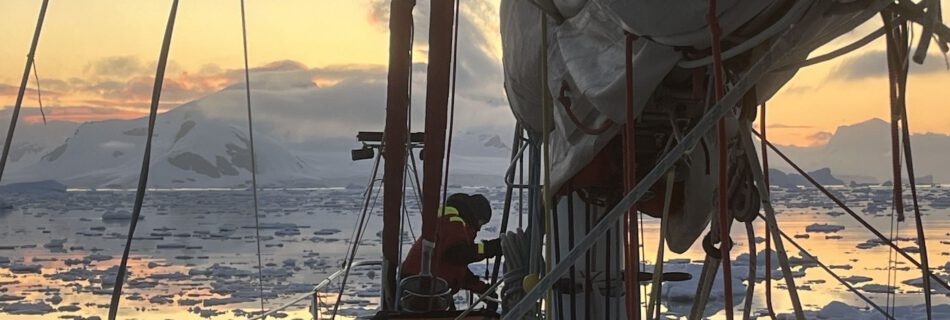

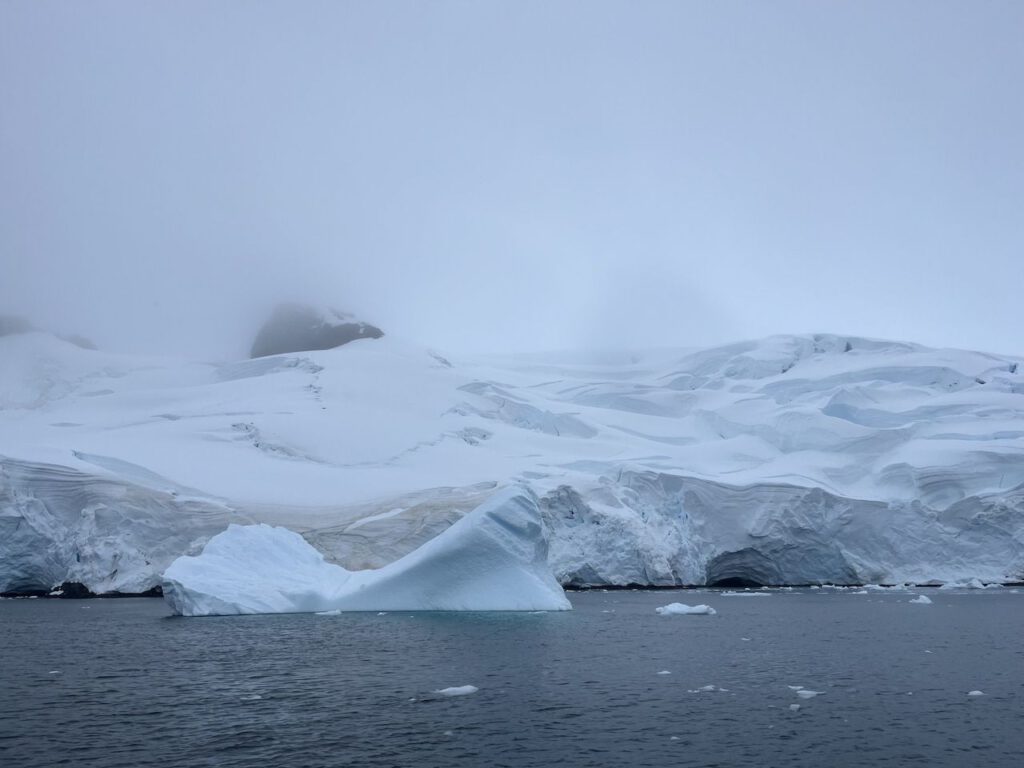

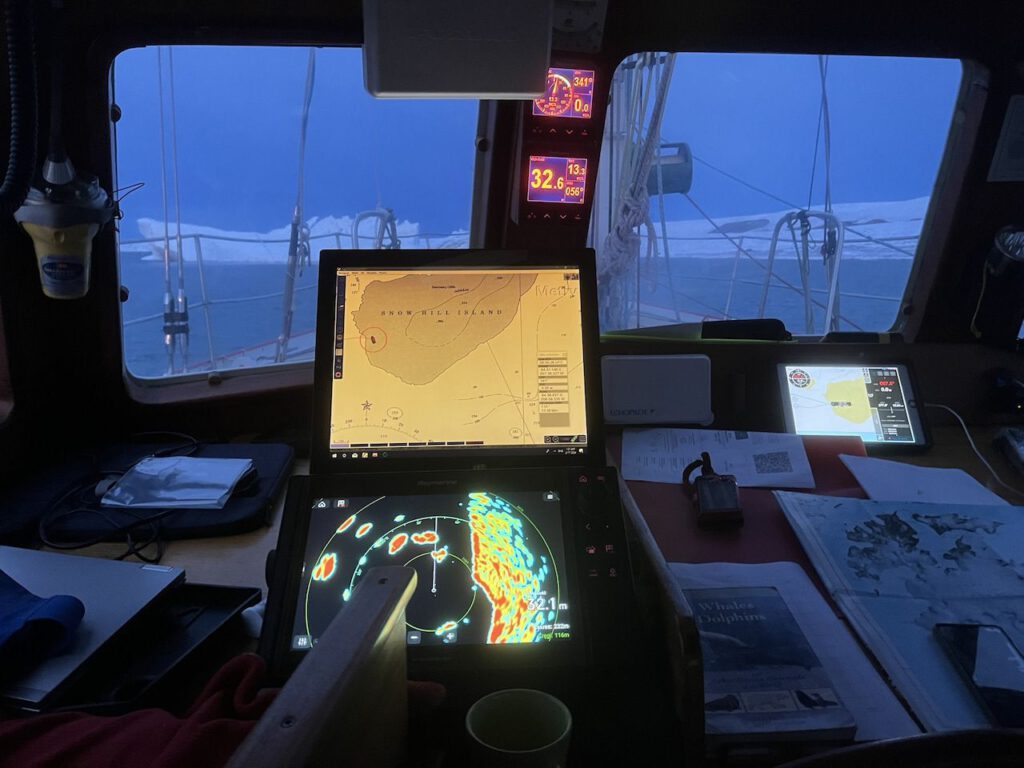

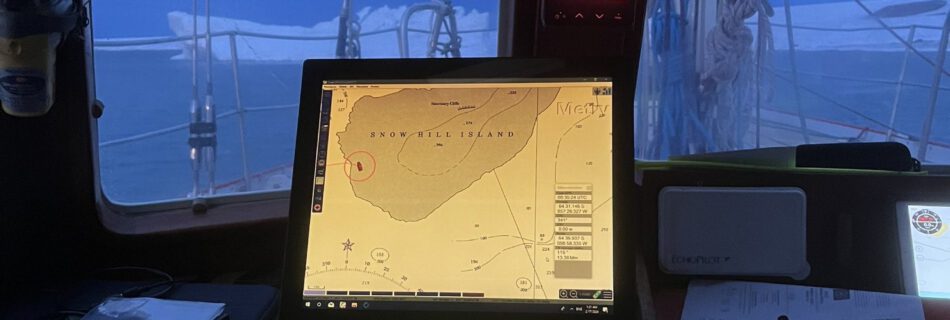

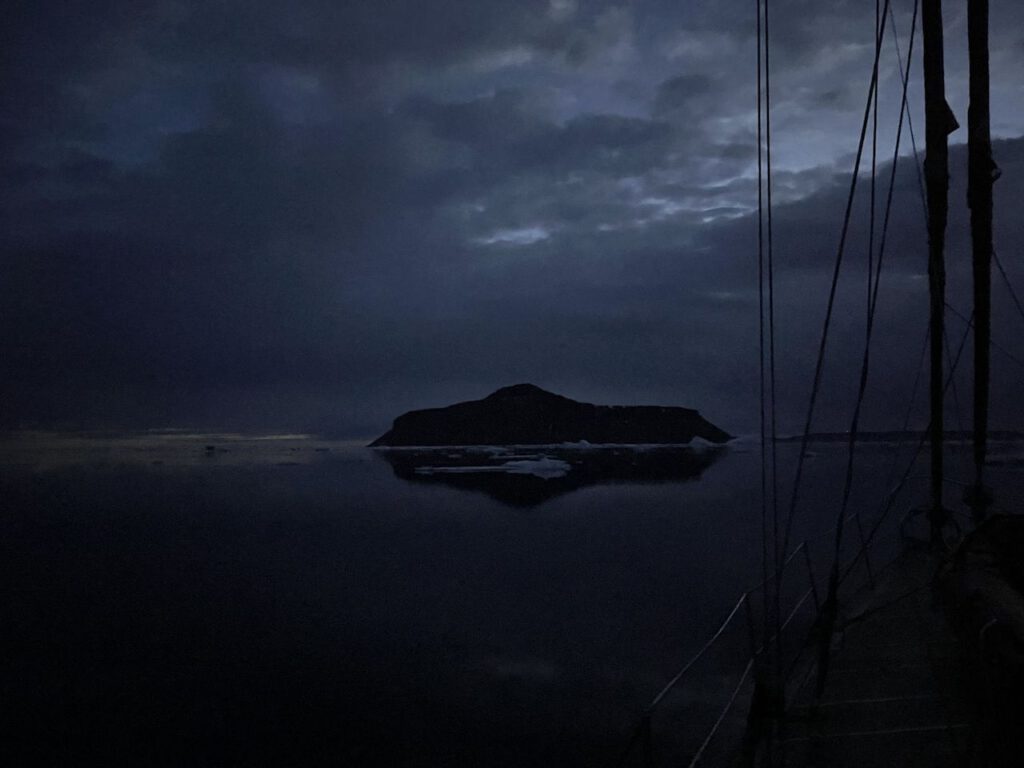

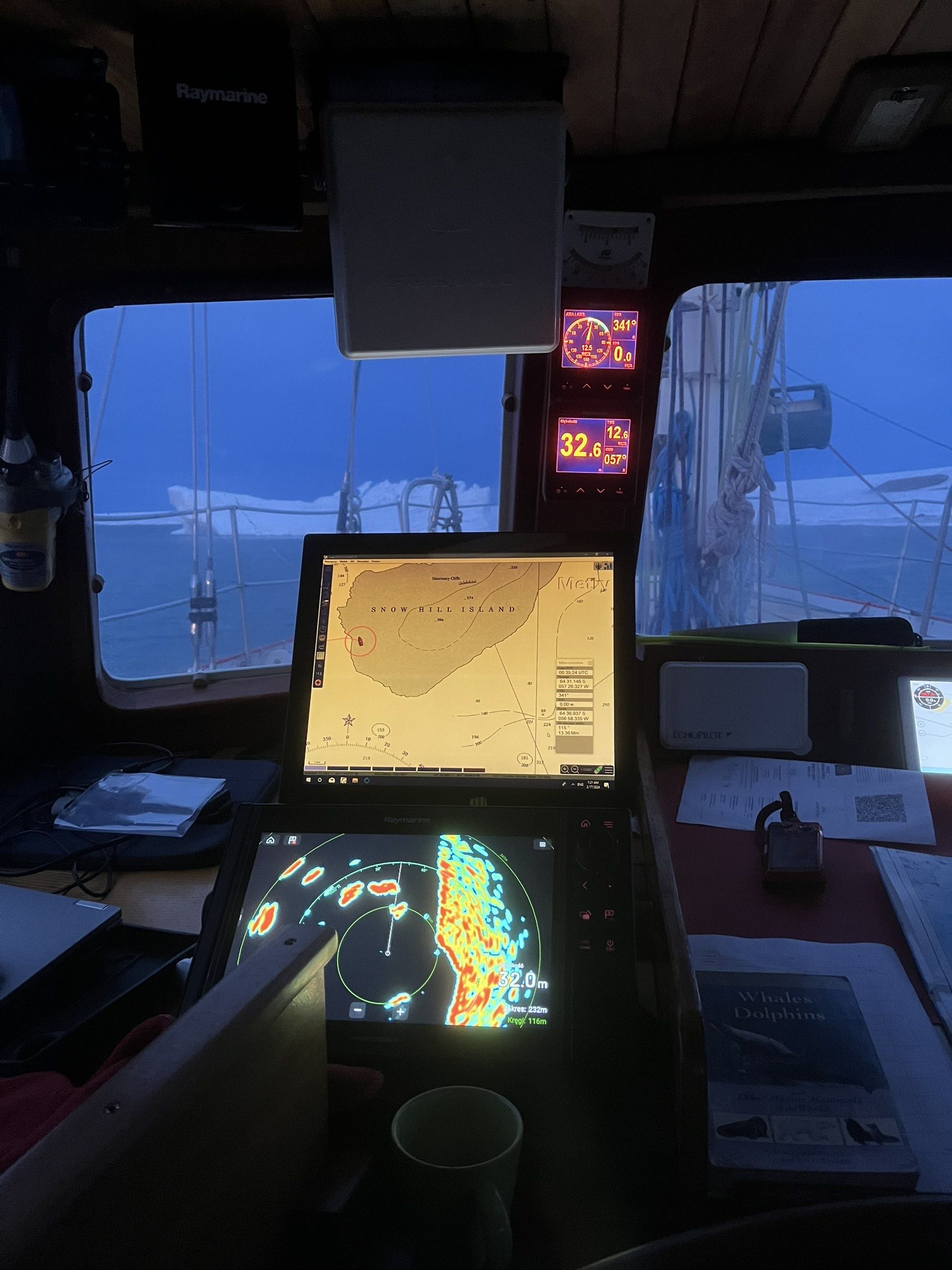

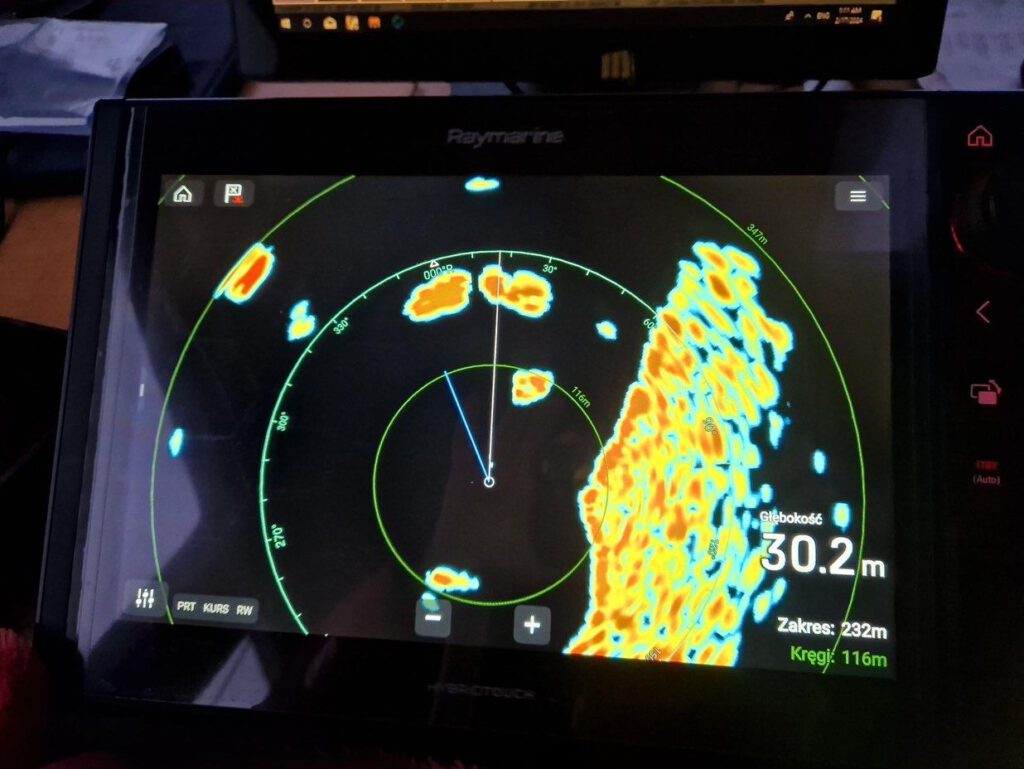

The gray remains with us south of the Arctic Circle, paired with decent waves but also sufficient wind, and we can set sail for a good four hours until we reach the north of Adelaide Island. We keep to the mainland, passing Isacke Passage, Hanusse Bay and the narrow Gunnel Channel to the east of Hansen Island. The clouds hang low, the little we can catch of the landscape along Hinks and Lawrence Channel is icy and glaciated. The wind from the northeast picks up to almost 40 knots, the search for an anchorage for the night is again not easy, but we find a small bay. The entrance is barely recognizable, icebergs are stuck on an offshore moraine. Only on the second attempt does the anchor hold, we have 80 meters of chain in place.

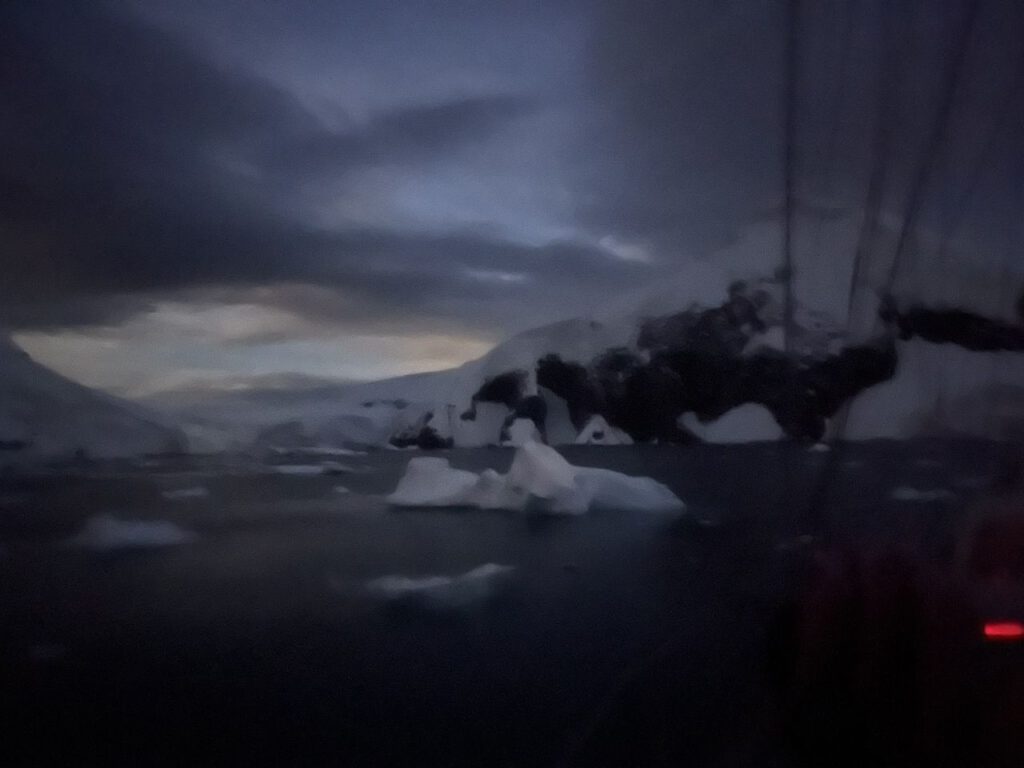

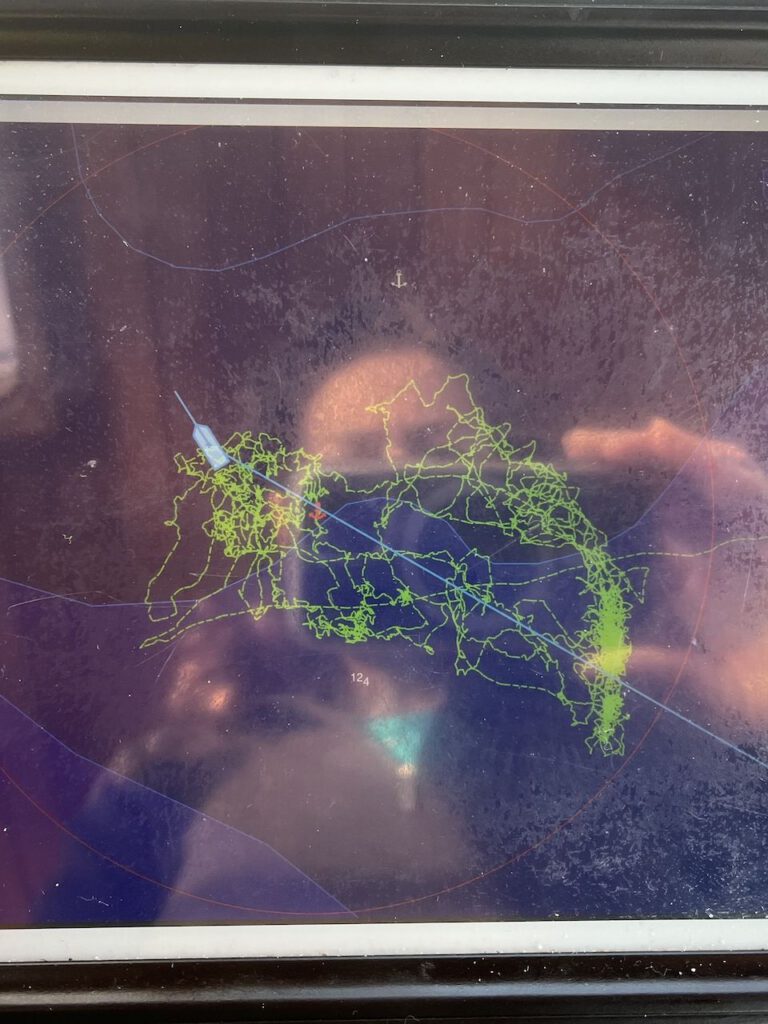

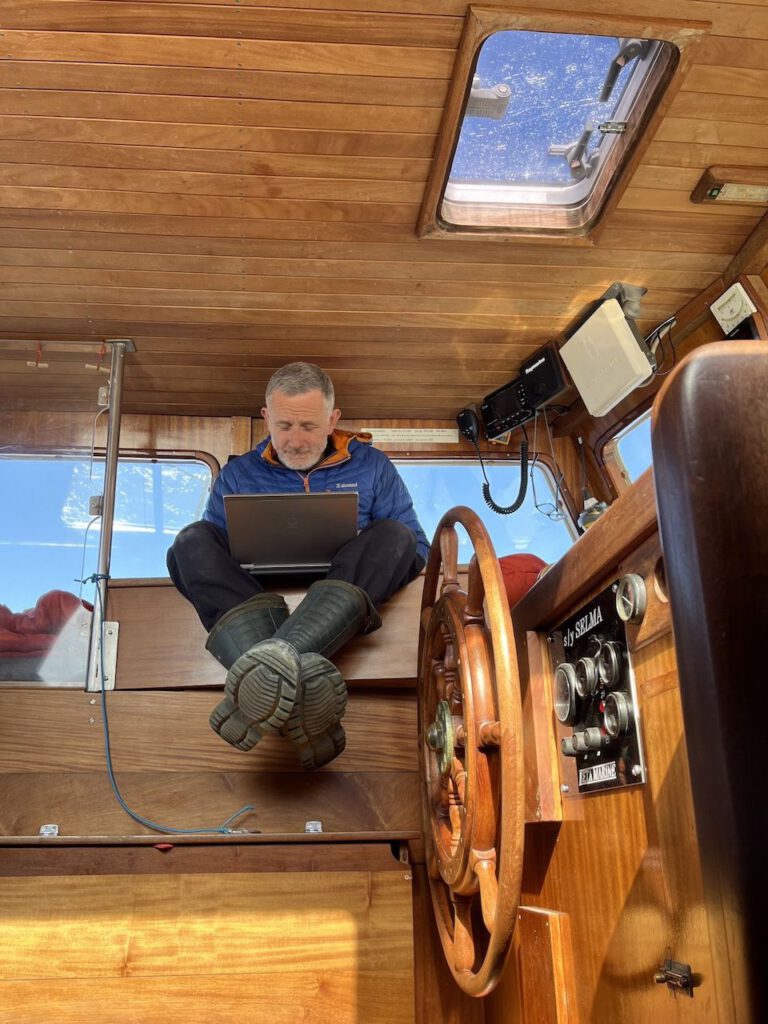

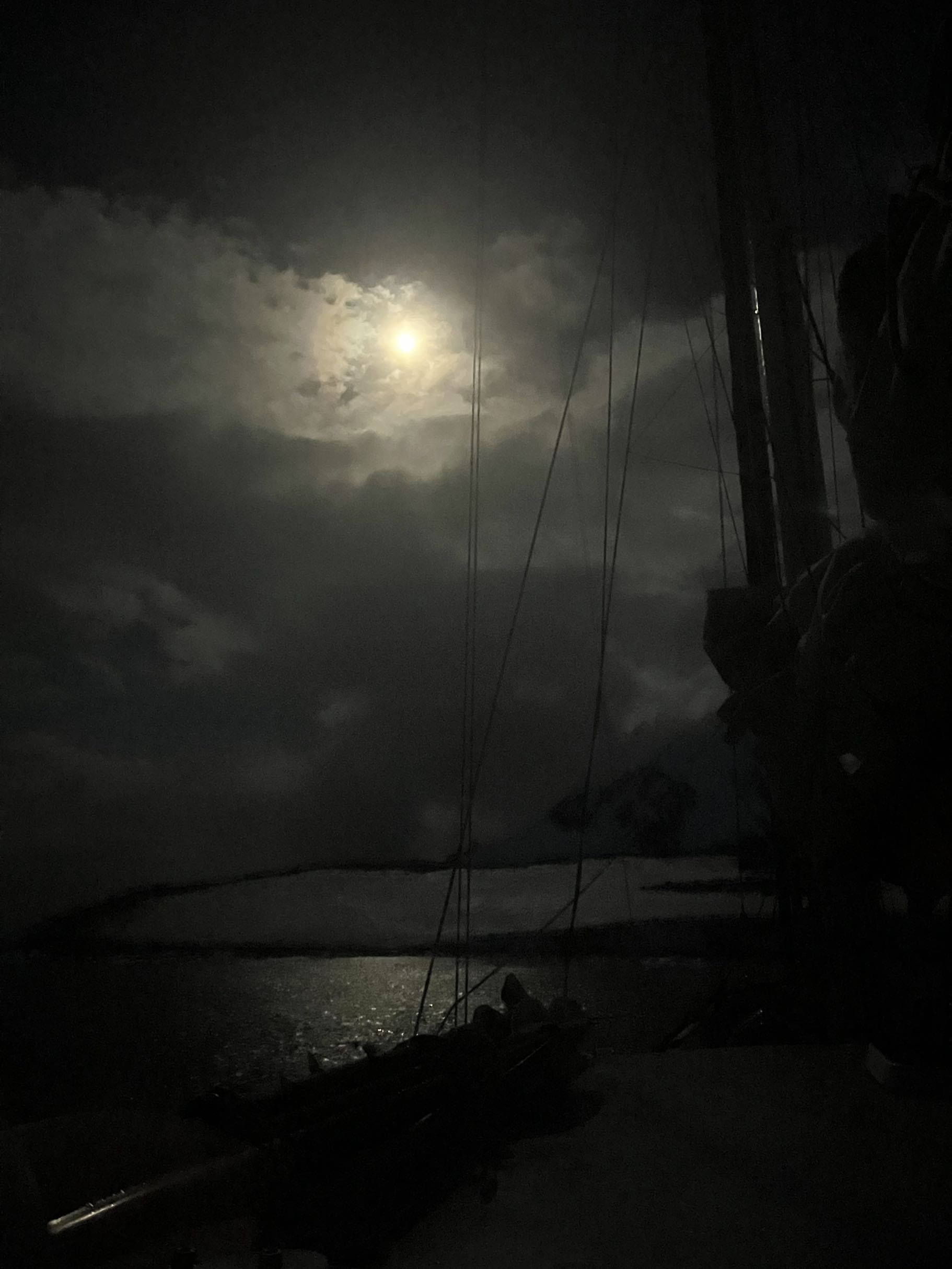

Unfortunately, the night is extremely restless. Ice is constantly drifting through the small bay, first in, then out again, and the icebergs that were stuck on arrival are also on the move again thanks to the tide. The anchor watch has a lot to do to keep the Selma halfway clear of them. At least we have support from the moonlight. The anchor is also tugging at the chain, the alarm goes off several times and more than once we think it’s going to break free. Fortunately, this doesn’t turn out to be the case, but hardly anyone on board really gets any sleep, and after a short night we set off again early before more ice drifts into the bay and blocks the exit.

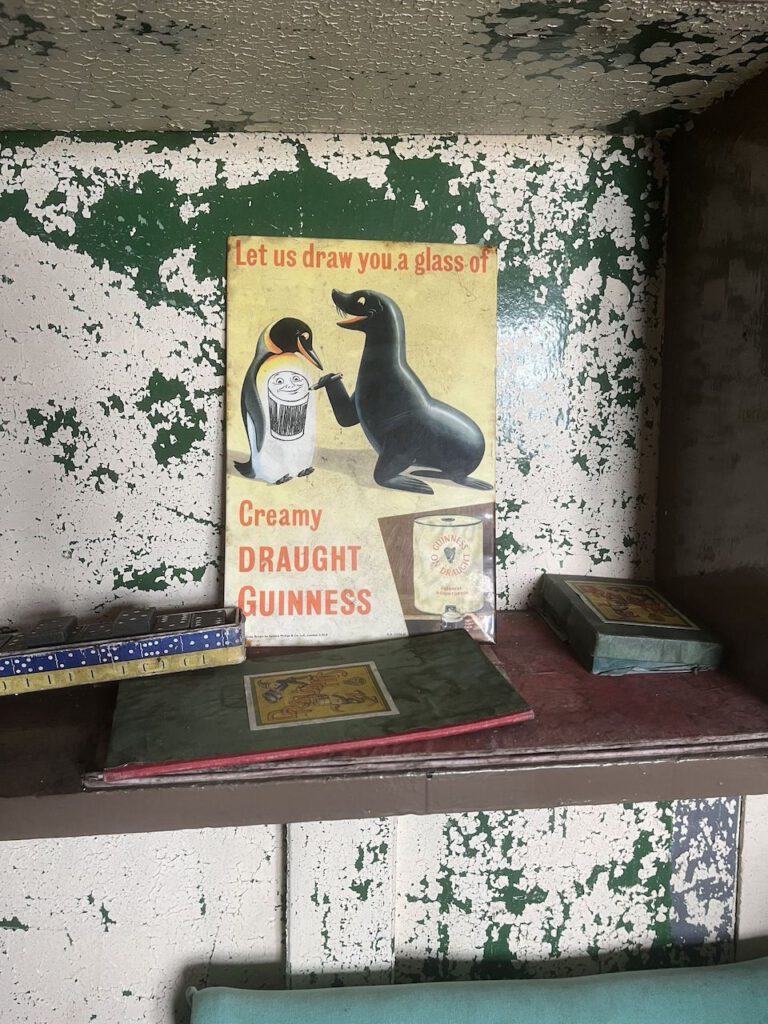

We have a coffee at four o’clock and weigh anchor at five o’clock in the morning. In the morning, the British station of Rothera comes into view. Alan was here a few years ago as a field guide and radios the station. Unfortunately, despite this supposed bonus, we don’t get permission to call at the base.

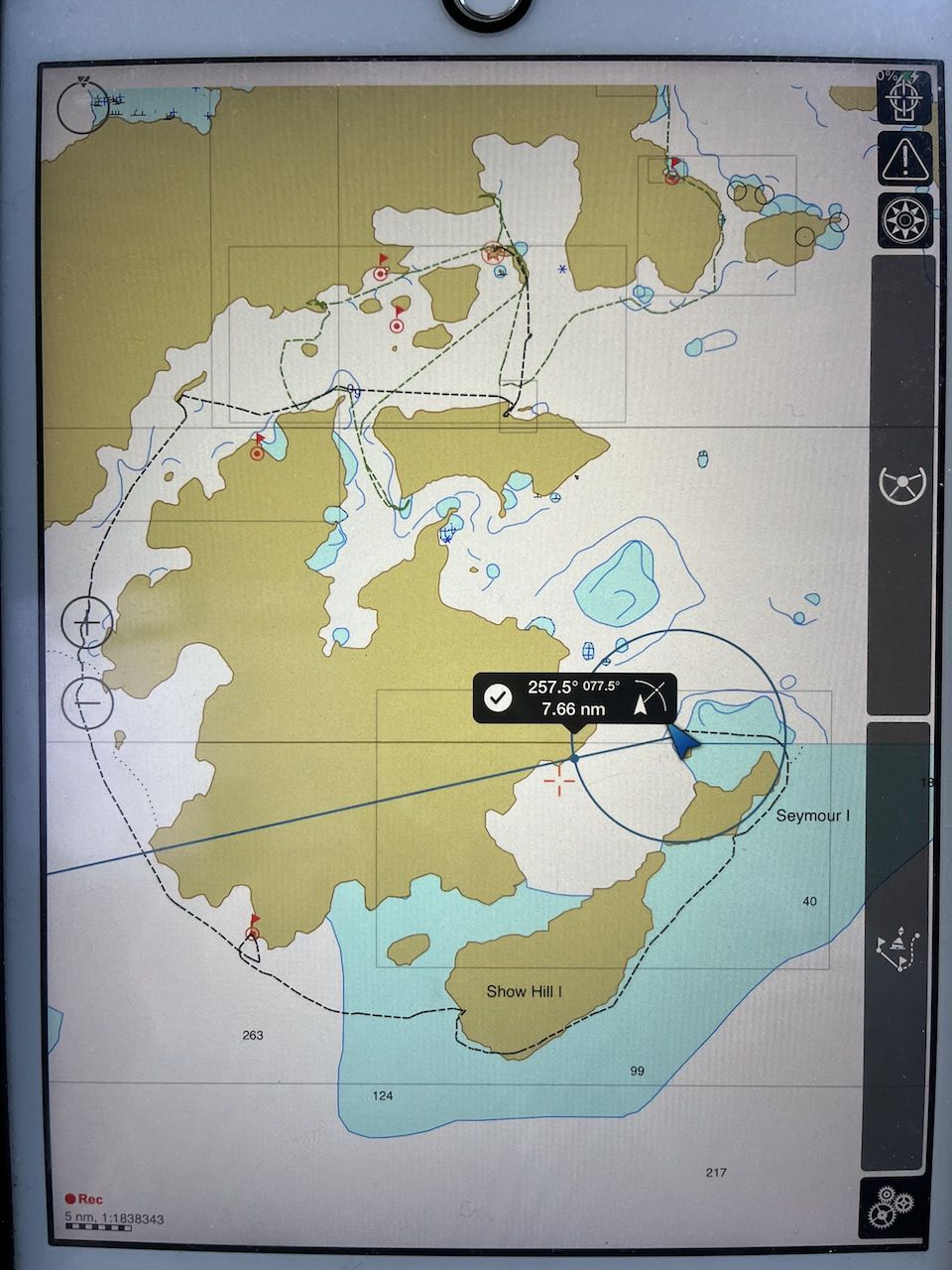

Leonie Islands

In Ryder Bay, we drop Ivan off on Leonie Island. While he searches for mosses there, we anchor off Lagoon Island and take the Zodiac across. Rothera asks us on the radio to keep an eye out for signs of the bird flu virus. On entering the island, the smell of decay is quite foul. Five not too long dead skuas lie in a narrow area around a small lagoon. This could be a sign of the virus, they are old birds, all without any recognizable external injuries. But a little later, we identify a larger group of elephant seals lying here lazily, dozing and digesting, as the reason for the foul smell. A large pile of huge brown bodies nestled close together. From time to time, a head rises briefly, sneezing or burping, looks at us troublemakers with huge saucer eyes, only to dive back into the cuddly confines of the others immediately afterwards. Or a fin is stretched out to scratch its belly or back. It’s wonderful to watch this peace and comfort, which is only disturbed when one of the animals thinks it wants to turn around, to which its neighbors first snort and complain, only to slowly jerk their clumsy bodies back into place. However, they are only clumsy on land – in the water, these massive animals move surprisingly elegantly and quickly. This is demonstrated by a specimen that suddenly appears directly in front of us while we are waiting on the shore for the Zodiac, only to dive down again immediately afterwards in shock at our presence and quickly seek refuge.

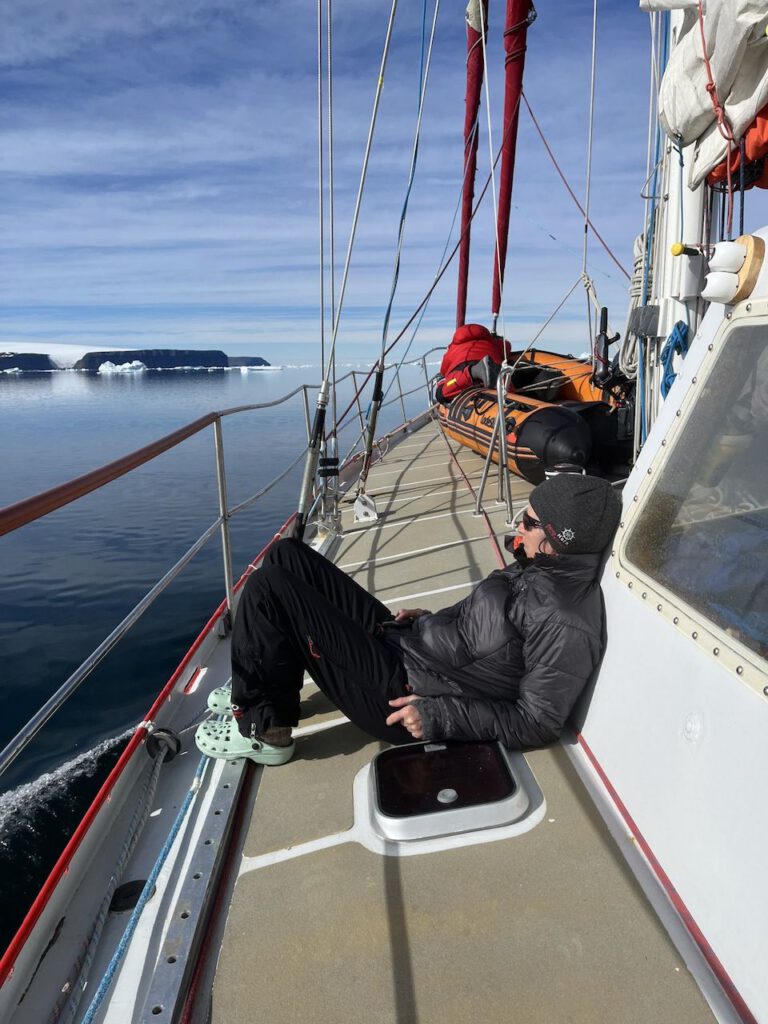

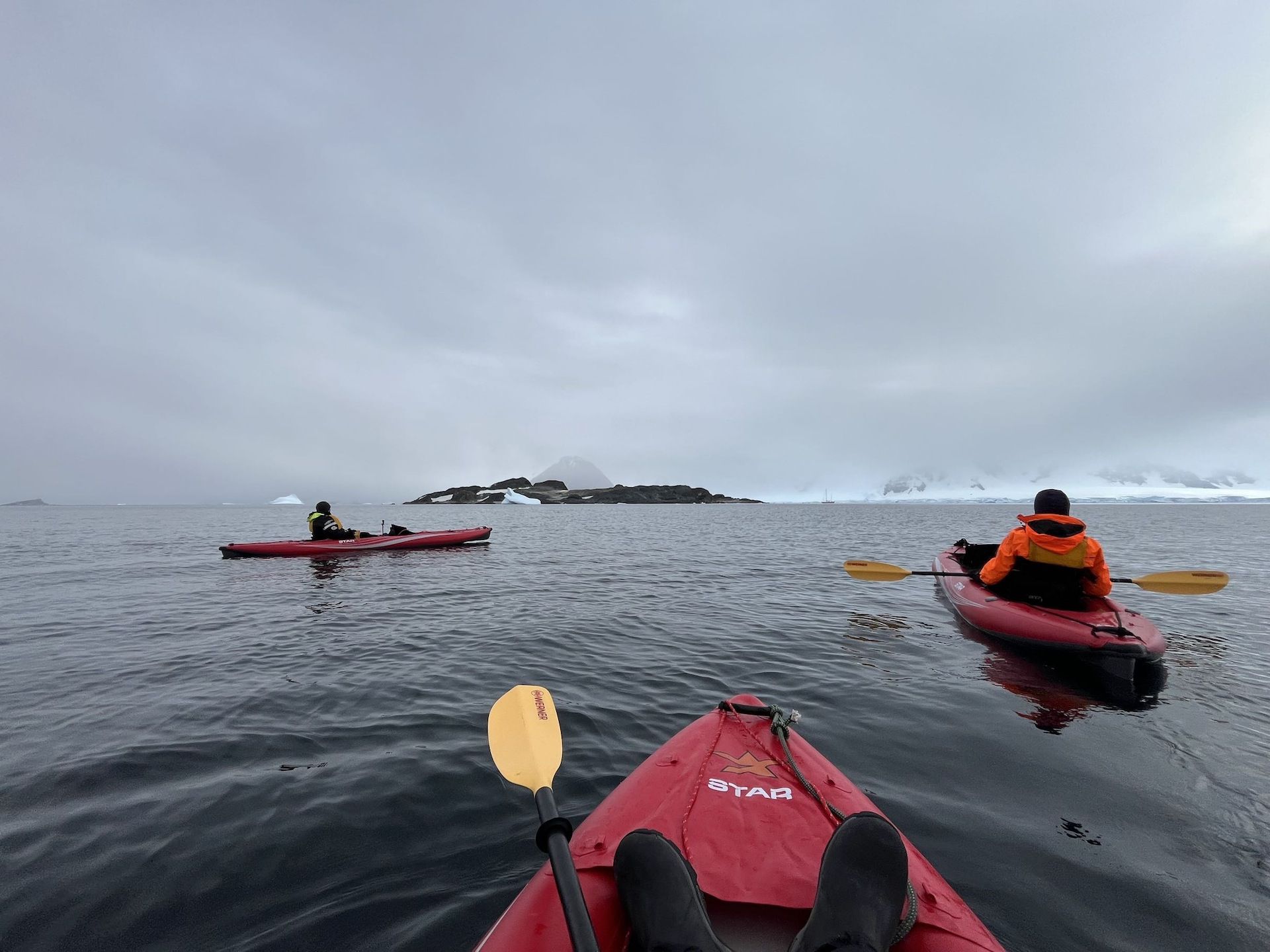

Kayak trip

We decide to spend the night here. So we still have time for an excursion around the islands. Some of us choose the Zodiac. Unda, Gerhard, Karen and I set off in three kayaks. We paddle our way around some beautiful icebergs and turquoise-blue ice floes and discover a small bay where we can observe penguins, Weddell seals and elephant seals at close range. But they take no notice of us. Just as we are about to head back towards Selma, Karen spots three whales that are obviously heading in our direction. Just the day before, Unda told me about her desire to meet whales in a kayak. To paddle with them. At eye level, so to speak. And now that’s exactly what happened. An hour of whale watching at its finest. The course lines of the whales and our kayaks crossed at just the right moment, and we experienced one of the most wonderful and moving moments of this trip. But Unda has already written so beautifully about this.

The encounter with these three humpback whales, especially the moment when one of them surfaced right at the bow of our kayak and right in front of my feet and next to us, its head, the huge body, shiny black, close enough to touch … it was breathtakingly beautiful in the truest sense of the word.

Strangely enough, we were neither startled nor afraid – there was simply no time for that. But it took a moment before we dared to breathe again, to really understand what had just happened, how incredibly lucky we were that Unda’s wish had come true in such a wonderful way.

Ivan, who we picked up again in the evening on Leonie Island, was also happy with his haul: the many samples of mosses, lichens and grasses. We actually felt like celebrating after this day. But a small glass of wine will have to suffice this evening, because we want to weigh anchor again very early the next morning and set off. To the southern tip of Adelaide Island, where we finally want to start our long-awaited mountaineering tour.