Offline at the end of the world ?

That’s what we thought before we started our journey, that was part of the idea. To be travelling at the end of the world and in a world of our own. Far away from world events, from permanent accessibility and availability, in seclusion and solitude. Completely on our own, alone in the here and now and in our own little universe.

I know and love this feeling from my first trips to the far north, to Spitsbergen. The world on a small sailing boat is a very special one anyway. Back then, you sailed from Longyearbyen out onto the Icefjord, and as soon as the radio mast was out of sight, you were out of reach yourself. Out of the world.

A few years later, reception reached all the way to the other side and as soon as you reached the bow of the Alkhornet into the Icefjord on the way back from the north, coming from Forlandsund, all the mobile phones on board suddenly started beeping like crazy, announcing all the news and updates you had missed with a multiple “pling”. And people who hadn’t even looked at their mobile phones for four weeks were suddenly sitting alone with themselves and their phones in some corner of the deck, staring spellbound at the display. They were completely absorbed. The mere availability of the phone awakened a need that had not existed all that time before due to a lack of opportunity. None of this had been missed before.

Times are changing. Even – and especially – in the remote regions of the world. Thanks to Starlink, even in Antarctica. Several thousand satellites in space provide even the most remote corner of our planet with an internet connection with a clear view of the sky. More stable and faster than in some German cities.

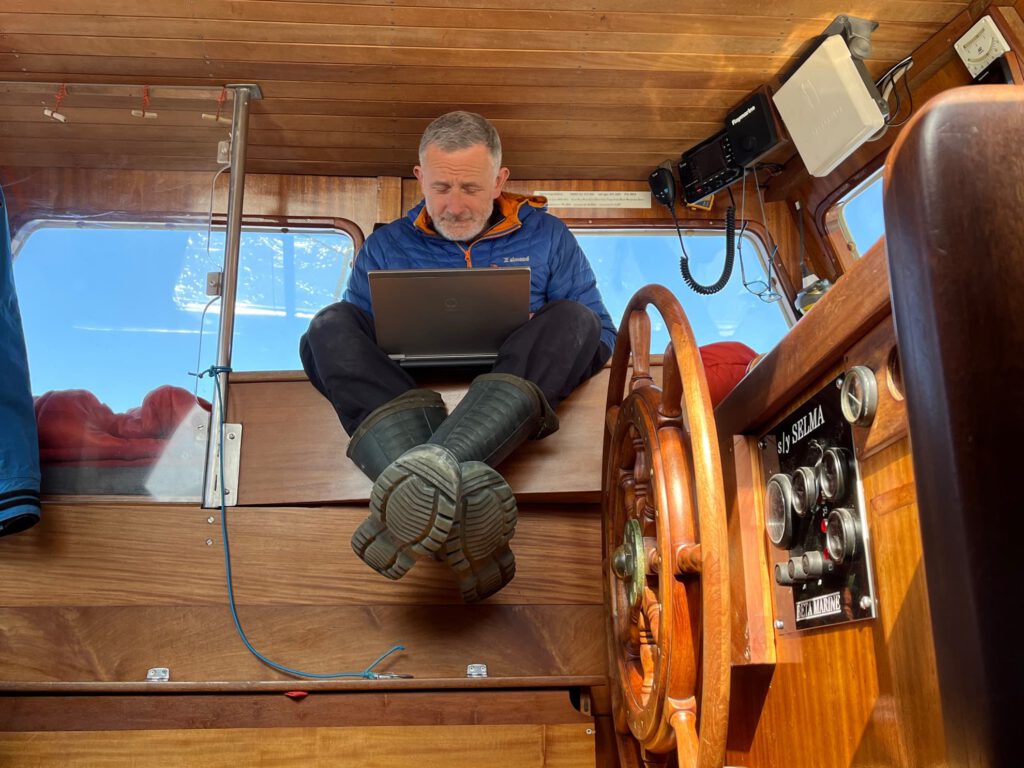

And so the surprise was great: contrary to expectations, Starlink has also been available on the Selma since this season. If the power supply allowed it, we were permanently online. We had access to all the information and – vice versa – it also found its way to us.

That changes a lot of things. Life and togetherness on board, the way we travel, plan and make decisions, and ultimately the entire journey.

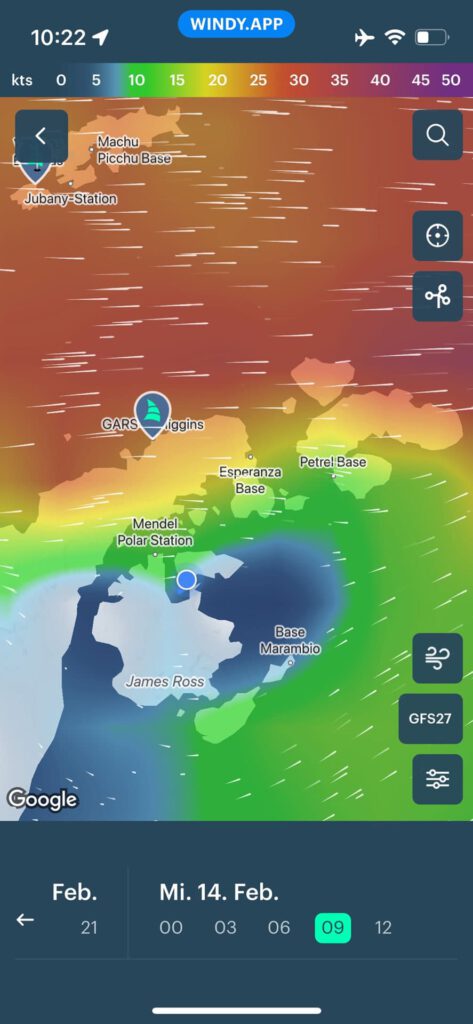

It’s neither good nor bad, it depends – as always – on how you deal with it, what you do with it. And there are two sides to everything. Of course it’s great to be able to call up the latest weather data at any time, to be able to plan and react in good time. That makes a lot of things easier and safer. But always knowing what to expect (even if the forecasts don’t always materialise) also changes the character of such a trip. With the information, everything becomes more predictable, more calculable. You inevitably subordinate yourself to them. On the one hand, it means more freedom, but at the same time less. Less adventure, less spontaneity, fewer surprises and fewer challenges. It completely changes the way we used to sail in remote, difficult areas – especially in the Antarctic.

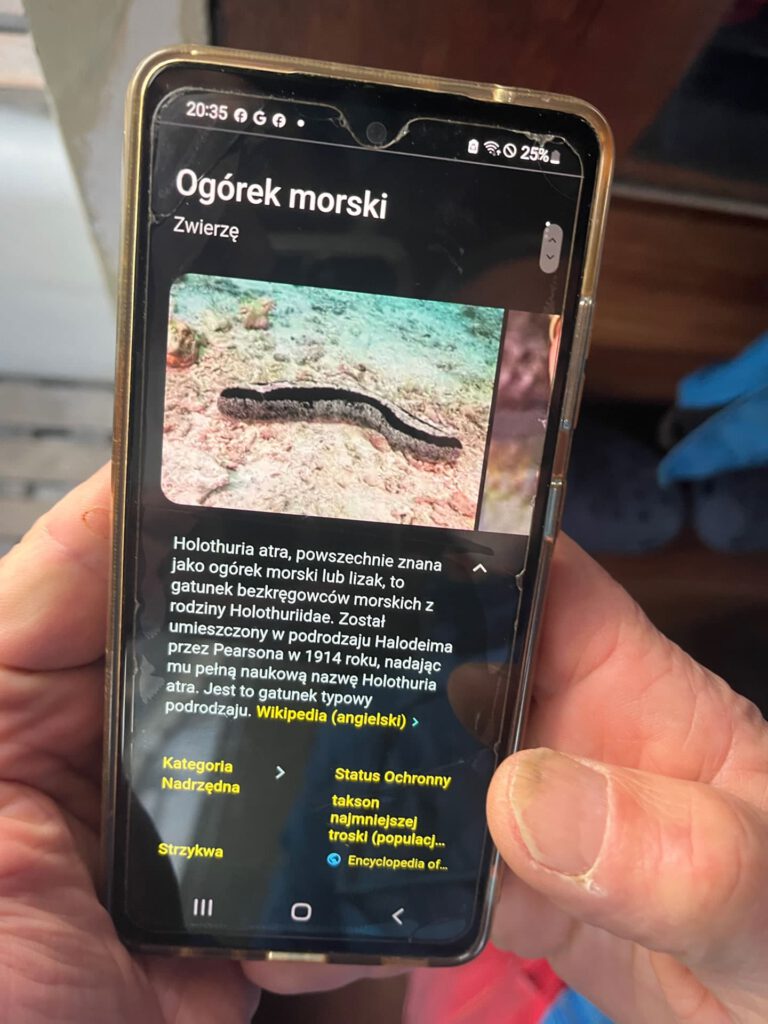

as well as sharing pictures, checking the internet for unknown found fossils …

And it changes life on board. Because we are ultimately permanently reachable. Because news reaches us from the world that we actually wanted to turn our backs on for a while. They seep into this very special, almost closed universe on board.

Because the familiar image from everyday life – a person with a mobile phone in their hand – suddenly finds its way here too. Sometimes three, four or more people sit next to each other in the saloon, each engrossed in their display. Instead of talking to each other. Because people are tempted to quickly check this or that or google it. To send, receive and reply to messages. Because the opportunity alone awakens apparent needs that would not exist without it.

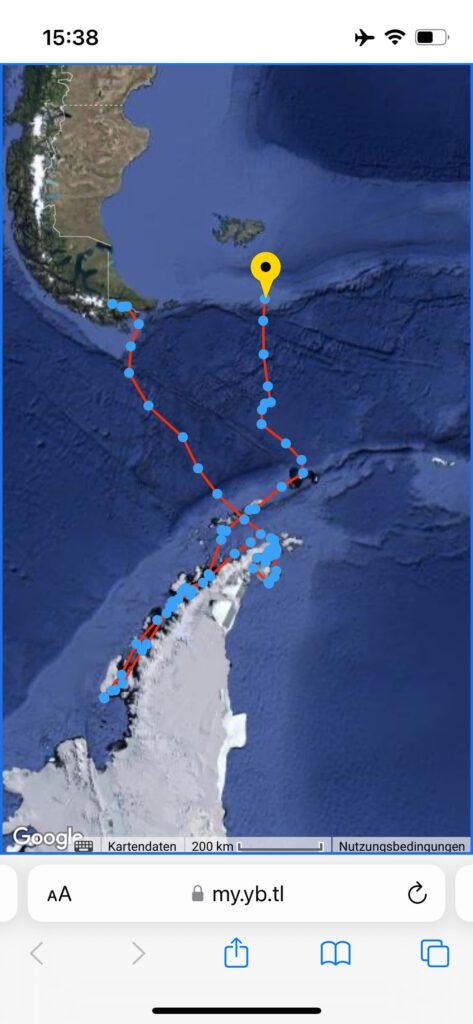

And, of course, it also changes our contact with the outside world. For example, the opportunity to share your experiences with others. While we had initially believed that we would only be able to send a sign of life, a few lines of text, out into the world once a week at most via Iridium, anything was now possible. Almost at any time and without limits. We could provide friends and families with messages and photos in real time. That’s nice, but also exhausting. It raises expectations that need to be met. It takes up time that you suddenly spend communicating with the outside world instead of the world and environment you’re actually in. You think about what to write, you sort and edit photos, read and reply to messages, post on social media … and you end up spending all this time alone with your mobile phone while reality passes you by at that moment.

But this seems to be part of it today. It’s hard to shut yourself off from it.

And that’s where Major Tom comes in.

Major Tom

My friend Tom, without whom this logbook would not exist. At my request, he agreed in advance to post the originally assumed signs of life and news – a few lines of text, about once a week – here on this website. So that families, friends, people who would have liked to join us but couldn’t and other interested parties could at least share a little.

Who suddenly got long texts and lots of photos. Which had to be edited and incorporated. Not just once a week, but much more frequently. A lot of input from me, from us, meant a lot of work and a lot of time for Tom.

In the end, the internet at the end of the world meant that this logbook is well filled. More extensive than ever imagined. It has many chapters, tells of many wonderful experiences and marvellous encounters, shares many unforgettable moments and pictures. That was (according to the feedback I received) great for everyone who stayed at home. And in retrospect, it is also a gift for us to have written all these reports and thoughts and to be able to read them here …

Without Starlink, but above all without Tom, none of this would exist.

For this, dear Tom, my and all our heartfelt thanks!