We’ve been on the road for almost a month now. Arrived far to the south. And ready for our planned tour ashore. Great anticipation for the five-member Mountaineering Team, consisting of Alan, Jan, Karen, Piotr and myself. After all, we took all the equipment with us, prepared it and tested it in Puerto Williams and Vernadsky.

Unfortunately, the weather gods were not quite so kind to us this time – they only allowed us a short window of suitable weather. We had actually planned to spend three days on land in order to ascend to the plateau of the mainland of the Antarctic Peninsula. Now we have had to change our plans: instead of the ice cap of the mainland, it will be that of Adelaide Island, and instead of the planned three days, we have one day and one night until the next morning. That’s a shame, but we are and will remain flexible and happily seize the opportunities that come our way.

Departure

Early on the morning of March 1, we weighed anchor off Leonie Islands. The rest of the crew kindly took over our watches and breakfast so that we could take care of our equipment. It’s always amazing how much space and storage room there is on a boat like this. We rummage through cupboards, lockers, under benches and in the spaces between the saloon wall and the side of the boat and fill the saloon with our things in no time at all: High tour equipment (ropes, harnesses, helmets, carabiners, ice axes, crampons and co), tents, sleeping mats, sleeping bags, stoves, pots, food, spare clothes and emergency equipment … pile up, are sorted and stowed in the rucksacks and sled packsacks. The rest of the crew flee to the deck or the wheelhouse in the face of the chaos we have created.

Meanwhile, we miss the fact that the Selma passes the south-eastern tip of Adelaide Island near Cape Alexandra in the Woodfield Channel and thus also the southernmost point of our journey at 67 47′ 700” S and 068 46′ 003” W.

We reach our planned starting point, the former Chilean station Teniente Carvajal on the south-western tip of the island, at around ten. Countless icebergs and an almost closed carpet of large and small floating pieces of ice, crushed ice, lie off the coast and we slowly and crunchingly make our way through them. It starts to snow and the wind blows uncomfortably. While the anchor drops, we get the pulkas and snowshoes out of the forepeak and all the equipment on deck. Everything is brought ashore in several stages with the Zodiac and heaved onto the old pier of the station, which is crumbling from the wind and weather.

The station has been abandoned for years. Several buildings lie derelict in the harsh Antarctic climate, with vast amounts of garbage, former building materials and debris lying around. In between, there are also huge numbers of fur seals that have taken over the area and, just like the skuas, are fiercely defending their territory, through which we try to make our way with our equipment. In one of the open buildings, we swap our rubber boots for hiking boots and leave our sailing gear behind. We find our way to the edge of the glacier behind the station and – again in stages – bring our pulkas, packsacks and rucksacks to the starting point, zigzagging between garbage lying around, slippery rocks, curious penguins, hissing fur seals, skuas attacking in a dive and sleeping elephant seals. After what feels like an eternity since we landed – it is now midday – harnesses and crampons are fastened, rucksacks and helmets put on, everyone is integrated into the rope team, the pulkas are strapped around our hips and we are finally ready to go. The rest of the crew wave goodbye and we set off.

Ascent to the glacier

The lower part of the glacier is bare, the ice is bare. It takes a while for our five-man rope team to settle in and find a common pace. Alan leads the way, first up the glacier to the ice cap – the Fuchs Ice Piedmont. After half an hour, we come across the wreckage of an airplane in the ice, the remains of a crashed Chilean Twin Otter. There are countless barrels of fuel lying around on the ice, looking back over the bay and Avian Island, nothing but white in front of us, the ocean dotted with icebergs on the left, the cloud-covered mountains of the Princess Royal Range bordering our field of vision on the right. It has stopped snowing. The next few hours simply consist of walking, step by step up the gently rising ice cap. Sometimes more, sometimes less evenly, we eventually find our rhythm. There are only a few snow-covered crevasses that run parallel to our direction of travel. A shadow or a minimal amount of packed snow usually gives us a hint of them. We collapse two or three times, but only up to our knees. Nunatak, our destination in front of the mountain range, is only slowly approaching, and here too the distances are fooling us, deceiving us into thinking we are close. The gray of the sky gets darker and darker. The sharp line between the ice surface and the sky, the contrast between the two looks beautiful. Over time, a band of clouds moves in our direction from the sea.

Around five, after three and a half hours, we decide to set up camp. Nunatak and the mountains are much closer, but we haven’t reached them yet. But we have to return the next morning and want to be back on the Selma by ten at the latest before the wind turns south and pushes the ice further into the bay.

Camp on the ice

We check the area around the camp for crevasses, set up the two tents, secure everything against the wind with snow poles, sticks, ice axes … tie the pulkas down. The snow melts and we hungrily enjoy our three-course meal of dehydrated trekking food straight from the bag in front of the tents: vegetarian pasta Bolognese, creamy pasta Alfredo and, to top it all off, chocolate mousse. Full and satisfied, we miss the forgotten whisky or rum just a little.

Despite our warm down jackets, it has become very cold, the clouds approaching from the sea have reached us and within a few minutes they have completely enveloped us. Whiteout. And time to crawl into the tents, these two little yellow dots in the vast, seemingly endless white universe around us. While we make ourselves comfortable inside, it starts to snow outside. It takes a while for us to get warm – the three men next door are probably cozier than Karen and me. We listen to the snow crystals trickling onto the tent wall and the Antarctic silence together for a while, until a quiet snore drifts over from next door and we too eventually fall asleep.

Eight hours of undisturbed sleep lie ahead of us: no watch, no maneuver, no iceberg, no anchor alarm … but I can’t really enjoy them. It’s a restless sleep, I wake up too often. The back also finds lying down for eight hours unusually long, so waking up at four in the morning isn’t so bad. If only we didn’t have to get out of the warm sleeping bag! We delay this as much as possible, melting the snow we had put in the awning in the evening in the red light of our headlamps and spooning warm muesli out of the bag. Only then do we peel ourselves out of the sleeping bag and into our clothes and shoes, which have remained reasonably warm under the sleeping bag – deposited under the backs of our knees during the night. In the morning, I’m glad to have so much space for two in the tent, the three next door have it tighter.

The first look out of the tent makes up for getting up early and the effort of peeling yourself out of your warm sleeping bag. It’s clear, the moon is still in the pastel-colored sky. The line of the mountain range is razor-sharp, above it a few veil clouds, pale pink, as if painted. The fresh snow has blanketed everything in white, the sea in the distance is a steely blue, as if frozen over. And in the east, the approaching day is already turning the sky golden. I can hardly get enough of it, but the air is freezing cold. Little by little, there is movement in the neighboring tent, one by one we peel out into the Antarctic morning.

Back to the sea

We pack up, take down the tents, load the pulkas and get ready to go. We put on everything we have to brave the cold. Putting on the crampons is easier without gloves, but it takes a long time to warm up your fingers afterwards. It’s good to finally start walking, to move muscles that have become stiff in the cold. There is a fine layer of fresh snow on our sledge track from the day before, which we now follow on the way back. With every step, the body becomes warmer, the muscles more supple, the feeling returns to the fingertips. The sky turns from light blue to deep blue, the snow in front of us a pale pink, already illuminated by the rising sun climbing over the mountain range. We have already been walking for an hour when we reach it, feeling the warmth on our faces, taking our first short break to stretch our noses out into the sun, enjoy the sparkle of the snow and breathe in this morning with all our senses. We laugh at our hundred-metre-long shadows, which will accompany us from now on, getting shorter and shorter, on the way back to the sea. The shadows of the pulkas also pile up meters high, those of the rope between us, which is actually almost taut, make high waves. Our caravan makes a funny picture. The snow crunches under our feet and we all have a grin on our faces. The way back is slightly downhill, so we’re going fast. The pulkas overtaking us slow us down briefly until we keep them in check again – now also with the tail tied into the rope. We soon see the wreckage of the plane appear as a glowing orange dot on the horizon, followed shortly afterwards by the blue barrels scattered across the ice. The icebergs on the sea grow with every step, the offshore island of Avian Island appears, and shortly afterwards we discover the masts and the hull of the Selma, glowing red in the morning sun. Although we were only out for a short time and really enjoyed our time ashore, the sight of it warms the heart. Down there in the endless expanse of this magnificent landscape lies our little boat, our home. The ice soon changes, the glacier becomes more choppy again, the station appears and shortly before nine we have rocky, solid ground under our feet again.

Our glacier tour on Antarctic soil was short, but exhilarating and beautiful.

We make our way through the fur seals and elephant seals again and gradually bring everything back to the pier. Meanwhile, the Selma has left her anchorage and comes to meet us. Ewa soon appears with the Zodiac and we bring everything back on board, trip by trip.

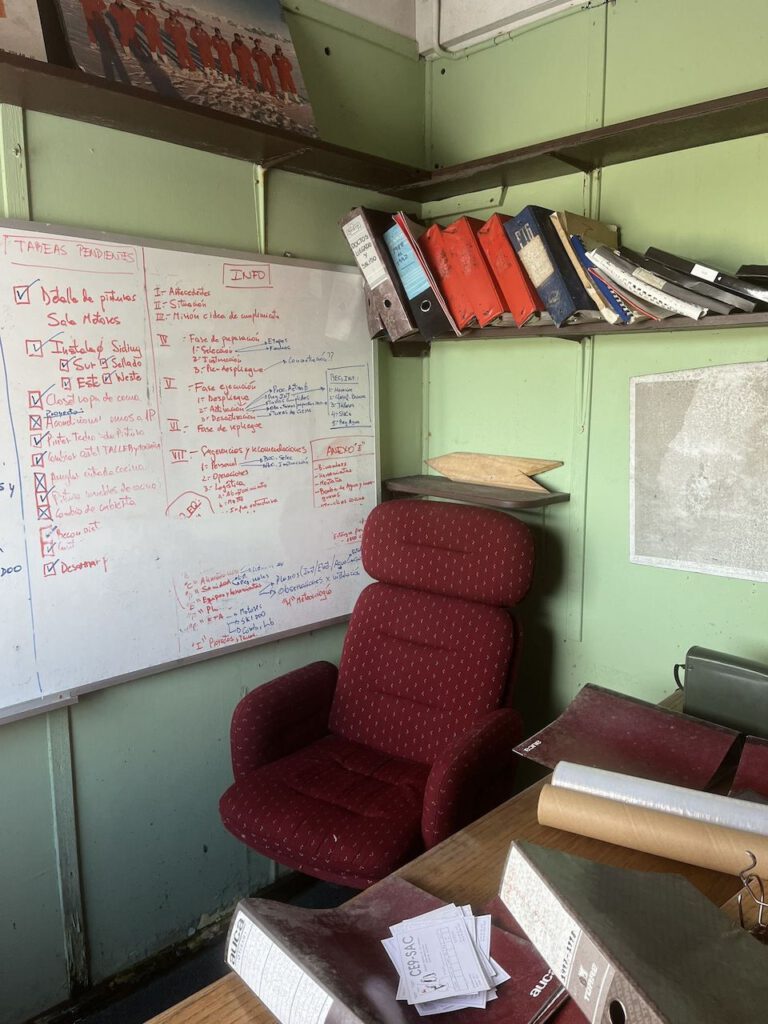

We still have a little time left to look at the Chilean base and wander through the abandoned rooms. It was used again in 2014/2015. Much of it looks as if it has just been abandoned, as if the kitchen and bar could be put back into use straight away, darts or billiards could be played … skis and equipment would just have to be taken off the shelves, and in the Commandante’s office there are still open folders on the desk and the stocks of Scotch tape and Pritt pens are untouched. An unreal scene. Back outside the door, the icebergs out in the bay gleam in the sun, fur seals bask on the warm rocks – quite a contrast to the garbage lying around or even the untouched endless white expanse of the morning just a few hours before.

A little later we are back on board the Selma, at home so to speak, and are pleased to meet the rest of the crew, exchanging our experiences of the last few hours over a coffee.

We stow all our equipment back in the depths of the boat and then, with the wind from the south, we sail on. This time, however, not to the south, but to the north.