Outside, the wind hisses around the masts of the Selma and the rain beats on the roof of the wheelhouse – it’s just plain bad weather. We’ve just managed to hide back here in the Argentine Islands in Vernadsky in time for the storm forecast for the next two days to blow in from the north on Monday afternoon. As we did on the way south, we will weather it here under shelter.

From Adelaide Island back north

At this time of year, it should be snowing rather than raining – it’s fall. This has already been clearly noticeable over the last few days. On the way here from the southern tip of Adelaide Island, it gradually got colder after a sunny, enjoyable day with the best weather. We had to deal with a lot of ice again and again.

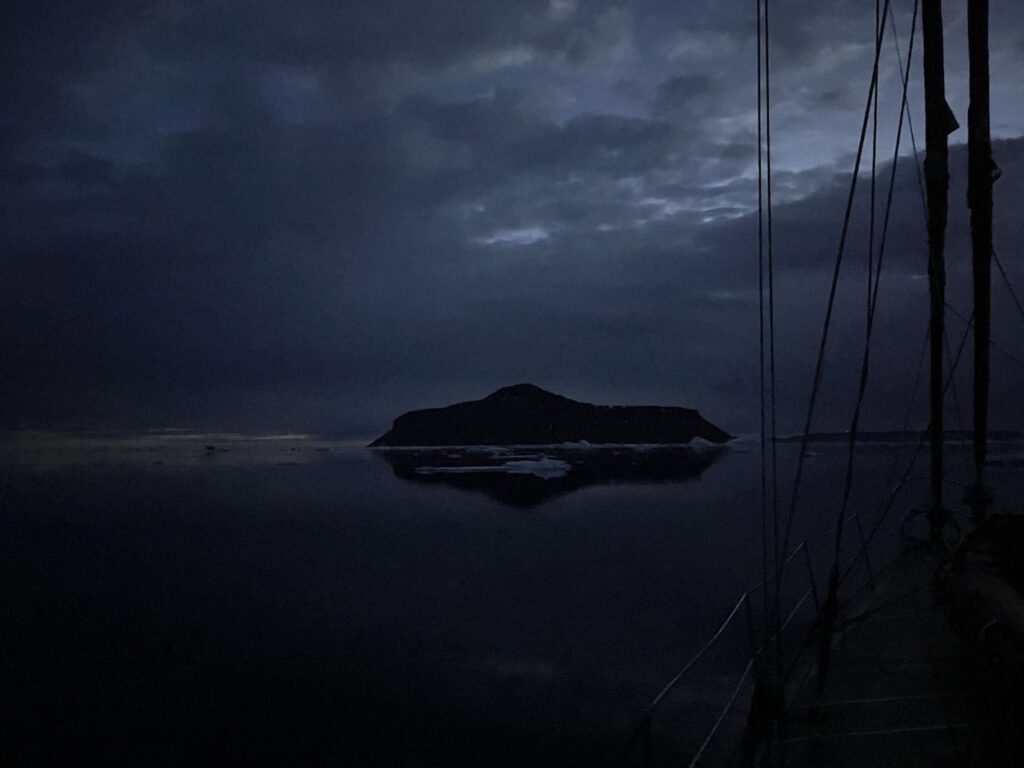

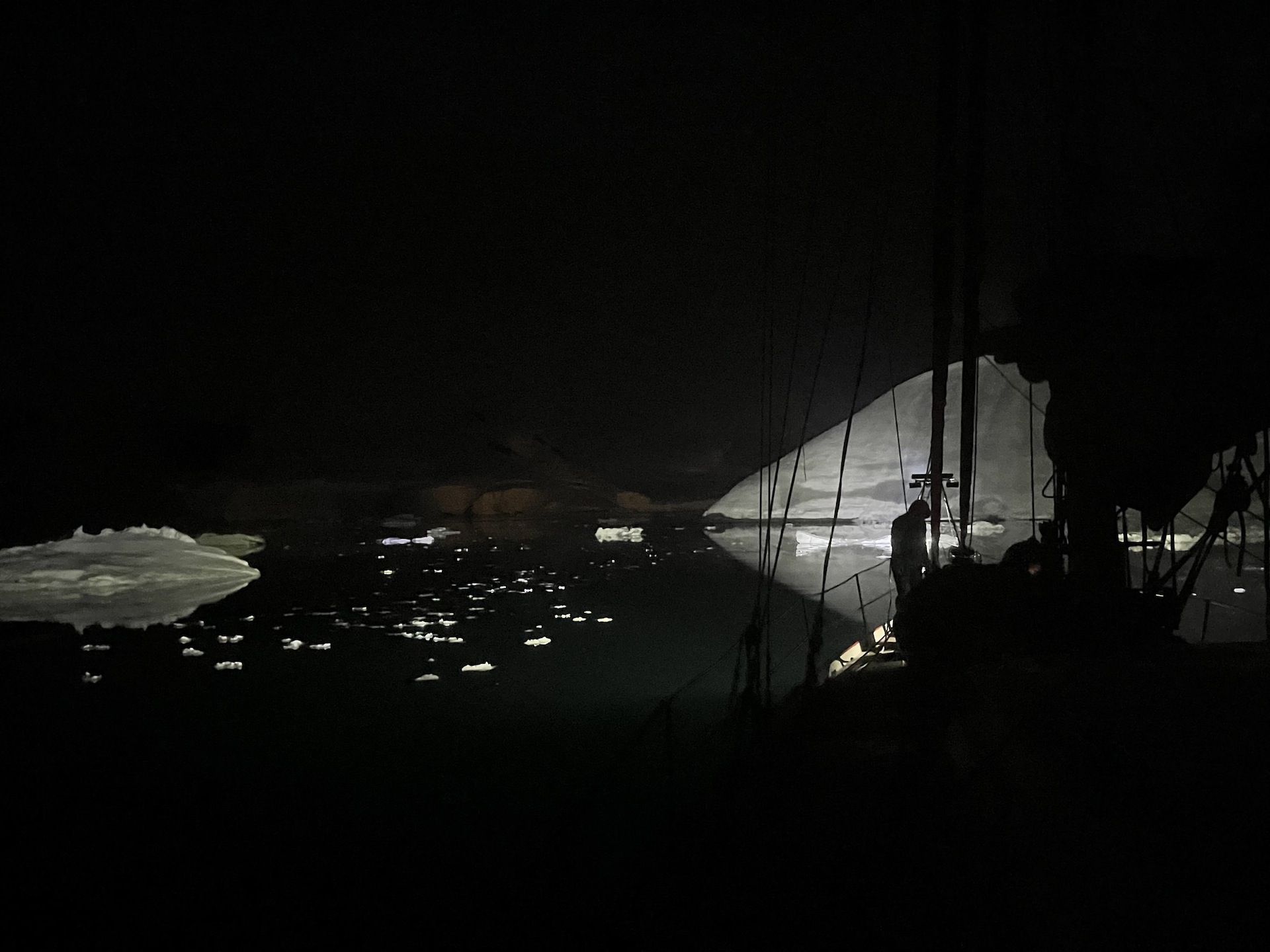

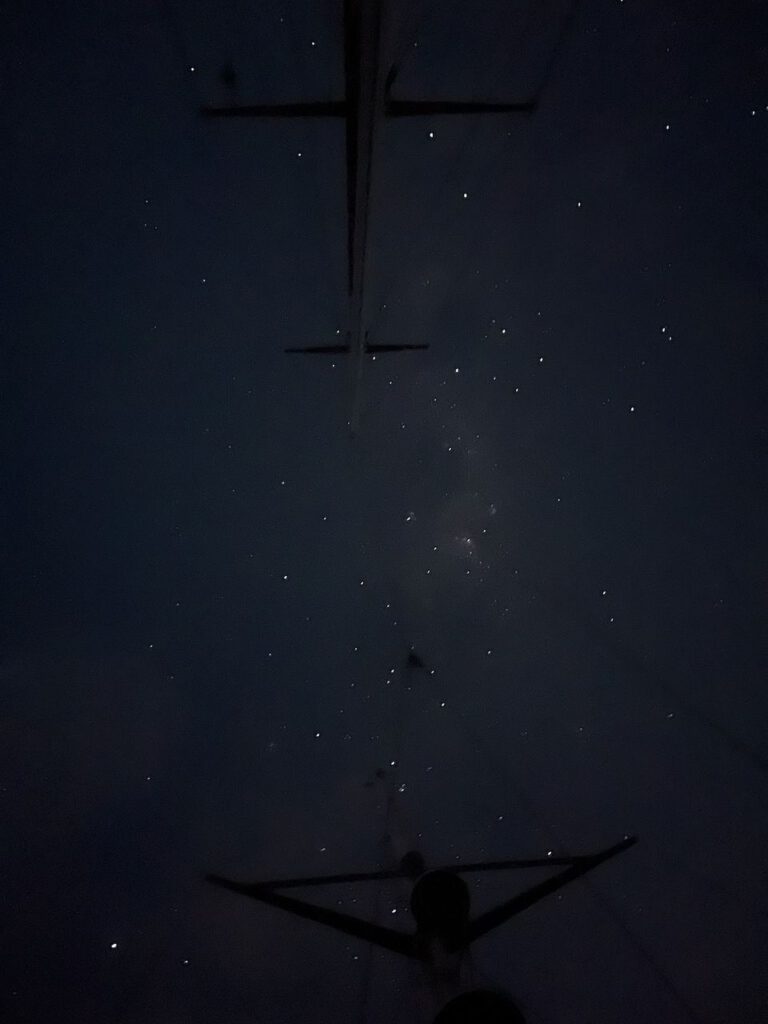

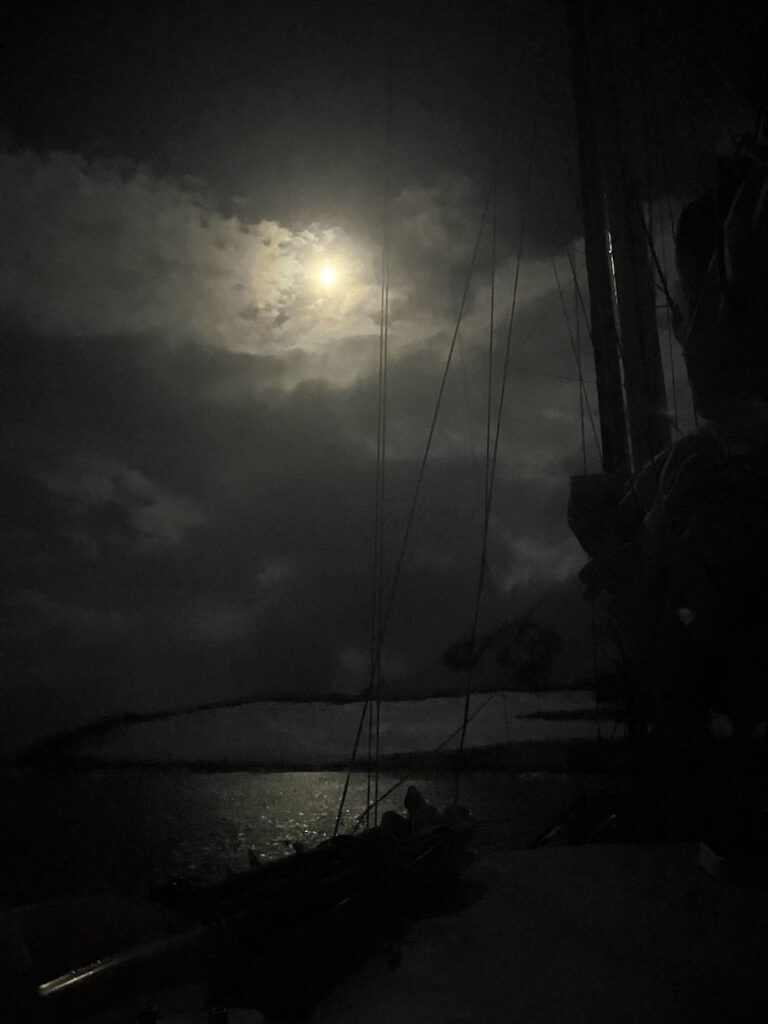

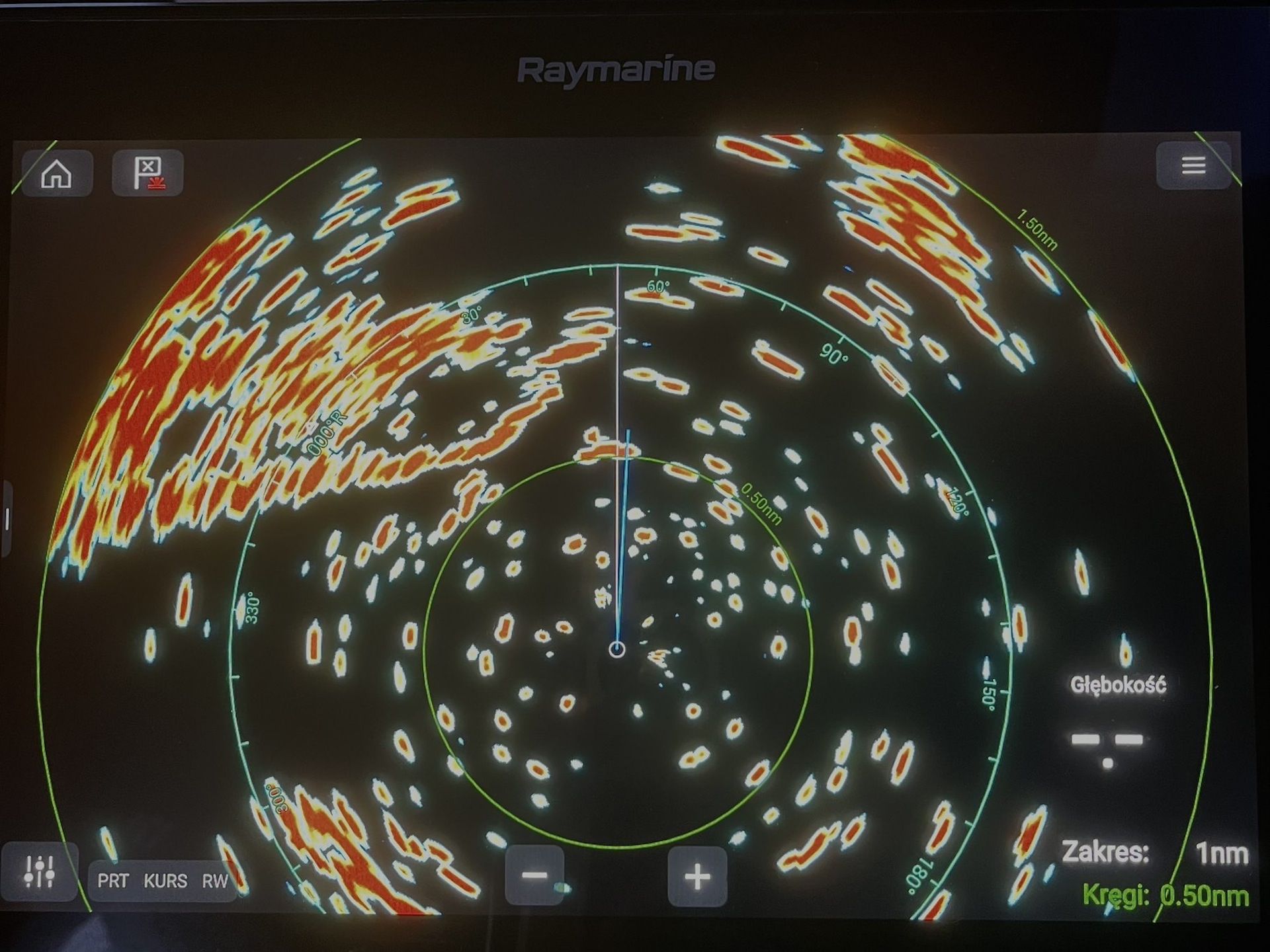

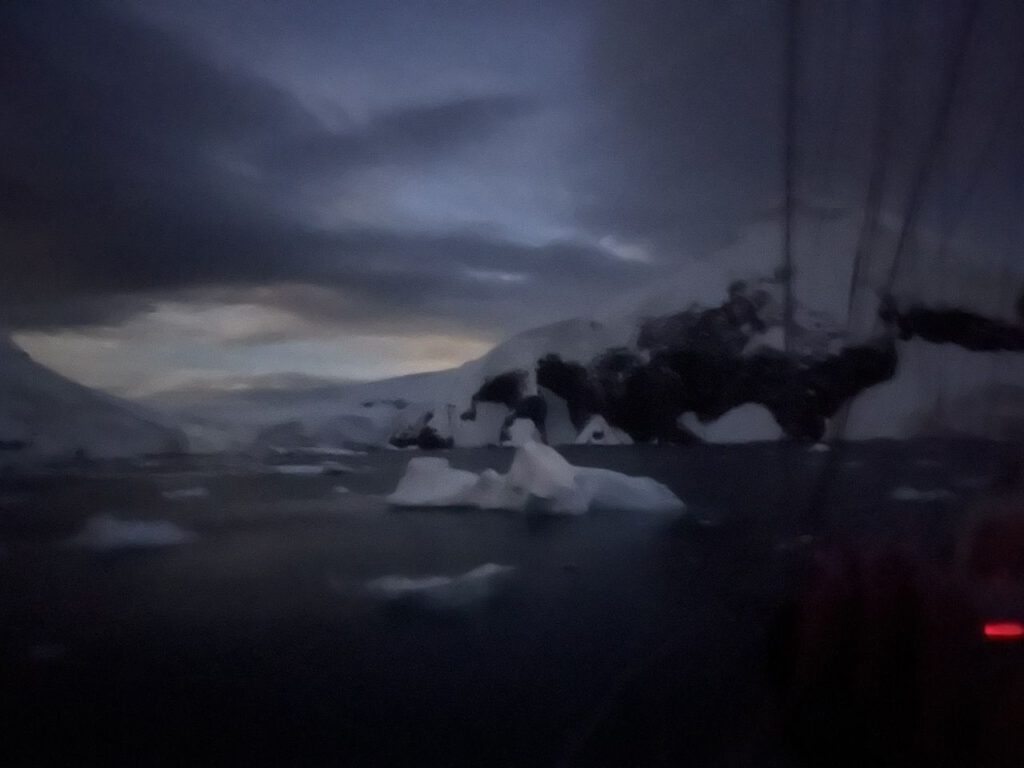

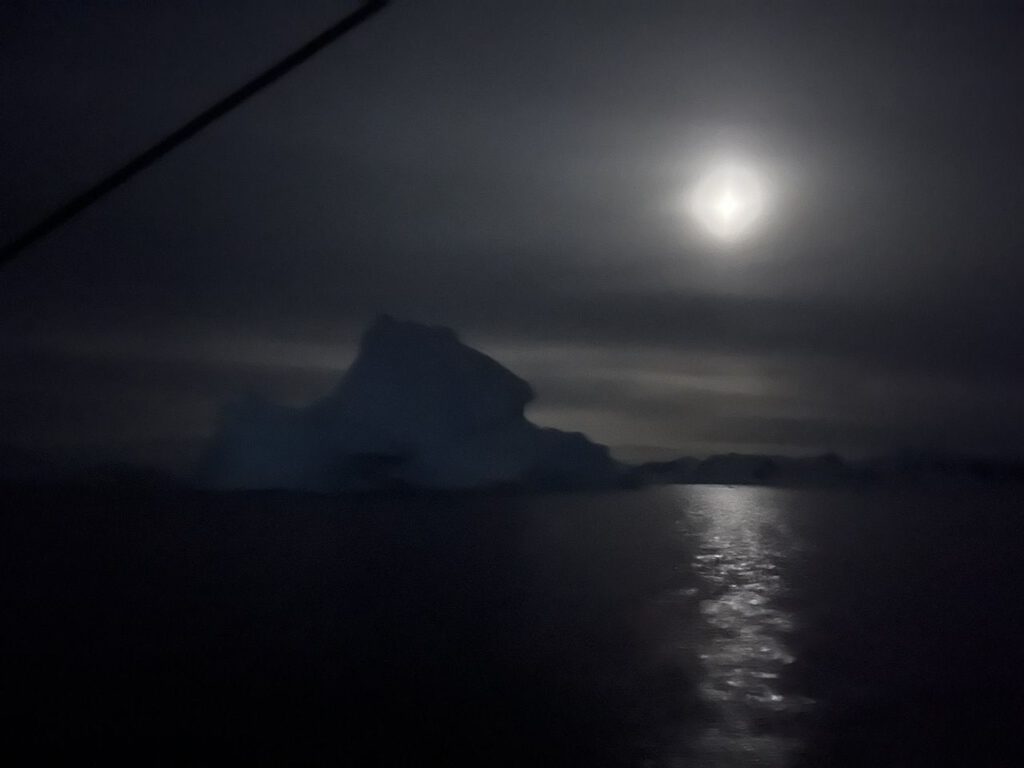

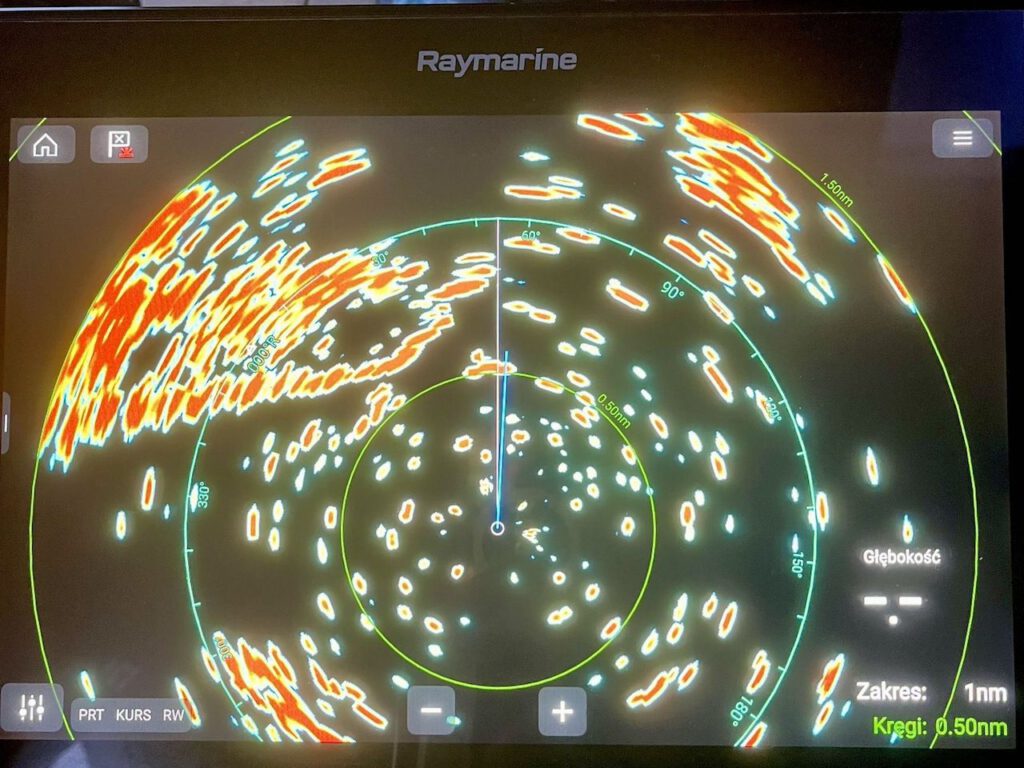

We actually wanted to round Adelaide Island and sail north again on the west side. But on the way back from our glacier tour, we saw numerous large icebergs and densely packed drift ice fields lying off the west coast from the ice cap. Together with the predicted stormy wind from the SW, these were not ideal conditions, as we wanted to sail to Vernadsky in one go without a break and thus also sail through two nights in order to arrive on time. Piotr therefore decided to take the route on the east side of Adelaide Island again in order to return north. It got really narrow in some of the channels and we had to turn back more than once because there was too much ice to pass through. Fortunately, there was always another canal as an alternative. This was also full of ice. But with very little speed, a lot of patience, a lookout on the mast, many turns of the steering wheel and a person at the bow trying to push the ice past the bow of the Selma on the left and right, we navigated – slowly, step by step (Piotr’s approach in most situations) – in a slalom through the ice fields. In the darkness of the night, we were just a tad more cautious and under the glow of our bow lights, supported by radar and sometimes moonlight.

Waddington Bay, Rasmussen Point

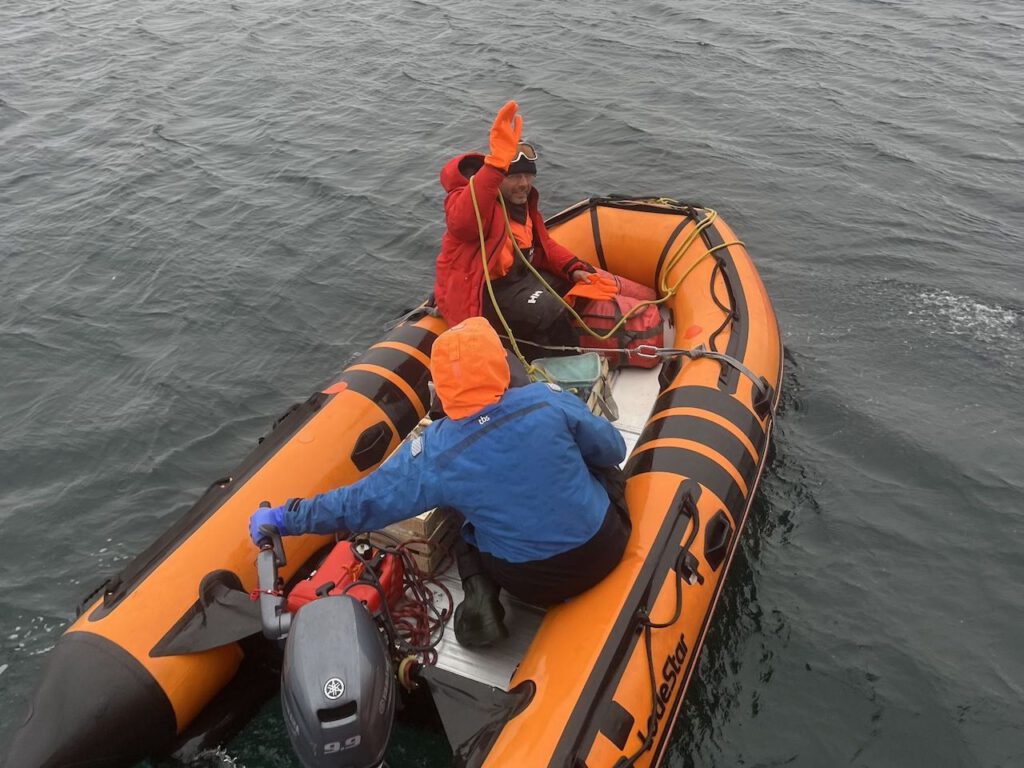

On Monday morning, we drifted for a good 1.5 hours before dawn, before heading for Waddington Bay in the morning sun. Here, too, the water was already covered in ice. Smaller fields of drift ice and repeated pancake ice (tightly packed round patches of ice with a slightly raised edge that look like large pancakes) accompanied us all the way to Rasmussen Island, where we dropped anchor. We wanted to take advantage of the sunny morning and the calm before the storm to go ashore. The Zodiac took us through the pancake ice to the island. Every now and then we had to help out with the paddles and break the ice or push it aside.

On Rasmussen Island lies a blue whale from the 12th century (!), or rather what is left of it. After such an unimaginably long time, that was quite a lot: not only the skeleton, but also the skin and blubber are partially preserved. A piece of nerve cord as thick as an arm protrudes from the huge jawbone, looking like wood, like the branch of a tree. While we gazed in awe at the whale and ice, Ivan took the opportunity to collect more samples. The island is a paradise for him, with lush, green moss cushions and colorful lichen adorning the barren rocks.

We gave Ivan time, moored the Selma and took the dinghy across to Rasmussen Point. On the way, we stopped at a large floating ice floe and boarded it for a short ice walk. A colony of Gentoo penguins awaited us at Rasmussen Point. However, they were not particularly enthusiastic about our landing, so we had to look for a less densely populated spot.

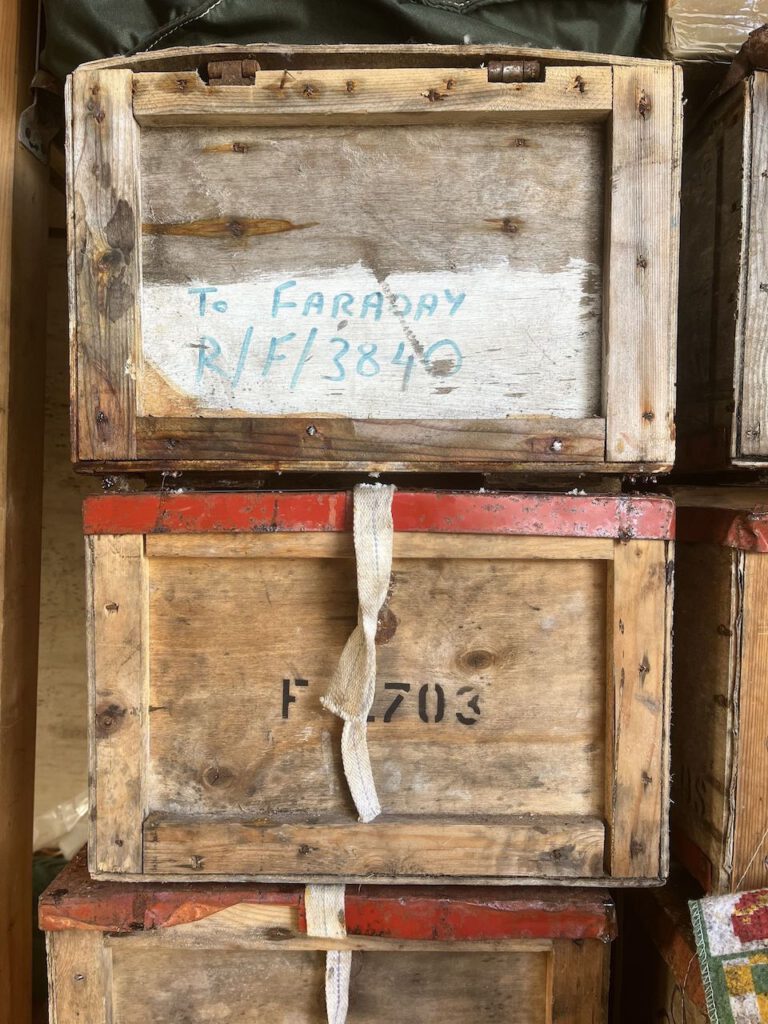

Once we had climbed up the rocks, we had a fantastic view. Icebergs, penguins, skuas, lush moss greenery, abandoned penguin nests … and a small refuge of the former British Faraday Station. The view of the neighboring glacier, its huge front and break-off edge was gigantic. But from the distance, the front was already approaching darkly from the southwest.

Into the safe harbor

We hurried to get to Selma, collected Ivan and his equipment from the island and set course for Vernadsky Station, a good five miles away. The weather changed within a very short time, the wind picked up to almost 30 knots, which didn’t make the journey through the thick ice any easier. However, a look through the binoculars from the mast was reassuring: a narrow dark strip along the coast of the Argentine Islands suggested that most of the water was open, which proved to be the case.

We passed the station just in time and reached the small bay, where another yacht, the Jonathan, was already well moored.

We dropped anchor and put out our shore lines, five this time, so that we were nestled close to the rocky edge of the bay in the lee. Always well observed by the landlord of the bay: the leopard seal. At first he played with interest between the rock and the boat, diving up and down, rolling and turning, swimming under the Selma, coming back and starting his game all over again. At some point, the dinghy became the object of his desire and he began to chase Ewa and Voy, ramming the boat once so that Ewa armed herself with a paddle as a precaution.

But at some point, all the lines were unfurled and secured, Selma lay calmly and firmly, the dinghy safely back on deck. And we were finally able to toast in peace to all the events of the last few days in the south: the crossing of the Arctic Circle, the southernmost point of our journey, the successful land excursion, the fact that life and togetherness on board is still wonderful and a celebration… The Neptunia Hendricks Gin from Ushuaia was just right for this, and Neptune also got his sip in thanks.

Misadventure I – Nasty surprise

We happily dropped Ivan off at the station straight after our arrival, along with his boxes and bags full of samples. We had spent the whole evening comfortably on board and were glad not to have to leave the boat in the bad weather, just like Piotr, who still had a sauna appointment.

The storm could be clearly felt throughout the night, shaking the lines again and again, hissing through the shrouds, the rain pattering on deck. The next morning didn’t look much better. 40 knots of wind, gray and wet. And the first look out of the wheelhouse held another unpleasant surprise in store for us: the dinghy was lying pretty flat in the water, the front chamber limp and deflated.

Apparently our neighbor, the leopard seal, had exaggerated his enthusiasm this time. We don’t know whether it was out of frustration that the orange thing didn’t want to play with him, or whether he perhaps got the sip for Neptune and couldn’t take it. Only that Piotr, returning late at night from the sauna, couldn’t heave the dinghy onto the deck on his own in the strong gusts of wind and didn’t want to get any helping hands out of his sleeping bag in the middle of the night. It can happen that quickly if you’re not careful. But getting angry doesn’t change anything and doesn’t help. We sat out the mishap due to the crap weather for the time being, had breakfast in peace, whiled away the day reading, writing, sorting photos …

When the steady rain finally turned into a gentle drizzle at four o’clock, we salvaged the broken dinghy. Hanging on deck, the extent of the damage became apparent: water was leaking out in several places. The leopard seal had done a great job (or the dinghy had put up such fierce resistance that it felt compelled to finish it off): all three compartments were damaged and showed clear signs of its sharp teeth – holes, slits, cracks across corners … Piotr’s verdict was total loss given the age and overall condition. Which saved us having to transport it to the station and repair it that day. We dismantled the dinghy and stowed everything in the forepeak, where it would find its final resting place for the rest of the trip. We hoisted the second, slightly smaller replacement dinghy on deck and made it ready for use. Incidentally, the villain who caused the damage didn’t show his face once all day.

Misadventure II

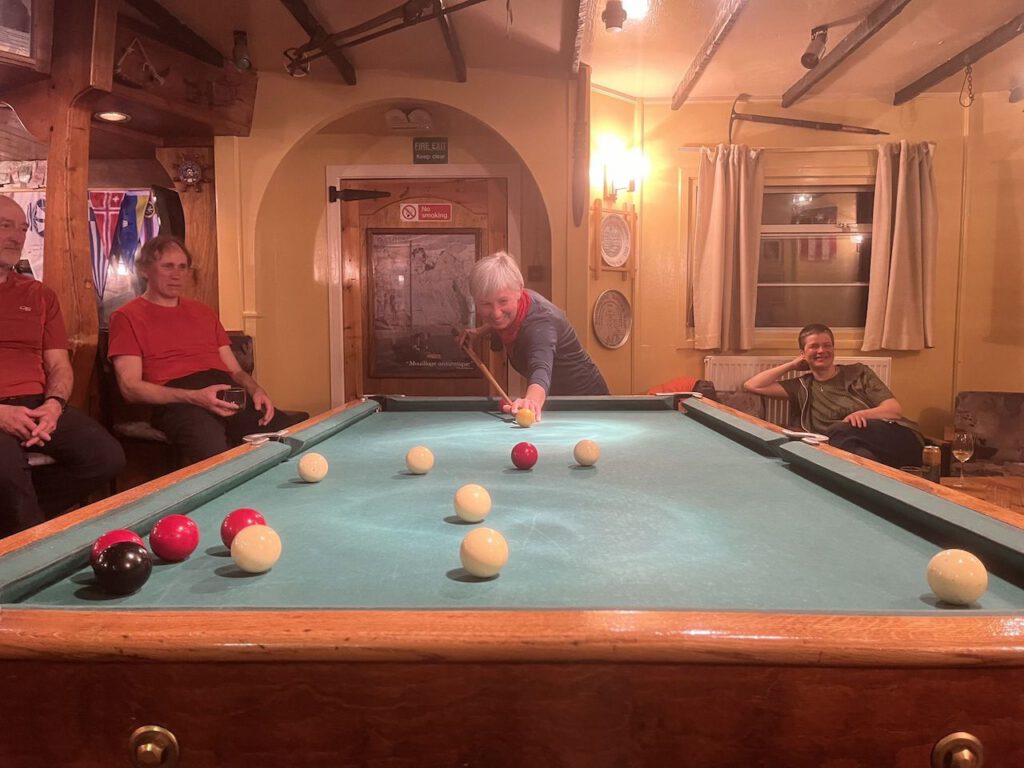

The day is already drawing to a close when we finally make our way to the station in two stages and can start the much-anticipated wellness program. The first group scurries straight into the shower and then into the sauna. Part two, which includes me, needs a little more patience, as we first have to untie one of the shore lines and then later deploy it again to let the Jonathan, which wants to move to another spot, out of the bay.

After that, the dinghy is free and we drive to the station. Once there, we pass the time a little, are invited in and have a glass of wine in the bar. When the rest of us call on the radio that we can come over to the sauna – we would just move a little closer together and somehow all fit in – we don’t need to be told twice: Karen, Ursula and I set off. As the dinghy is at Selma, we decide to take the land route through the penguin colony for the sake of simplicity and speed. Ivan hands us two large water canisters and tells us we just have to cross the snowfield and then scramble over the rocks.

The light from the sauna shines temptingly towards us. The penguins indignantly avoid us, some of them are in such a hurry that they slip. When they scold us and stumble away, you can’t help but laugh. But my laughter fades a moment later when my feet suddenly lose their grip. The snow has given way to a dangerous mixture of bare ice and penguin guano softened by the rain, which the soles of my wellies can’t cope with. I slip and slide down the slope past Karen. At the end, the waves crash against the ice. I definitely don’t want to land there and try to hold on somewhere, but wet ice and muddy penguin nests prove to be pretty unsuitable. My pants are already completely soaked. In the end, it’s a big pile of guano in which my hands find a foothold. I somehow come to a halt, scramble to my feet again. My trousers, my boots, my towel, my hands … everything is completely smeared. Karen and Ursula also get a few good splashes as I shake my hands and try to remove the worst of the dirt. We are greeted at the sauna with a grinning “You look like shit!” and lots of laughter. That’s what you get for laughing at stumbling penguins …

I smell like a whole colony of penguins, take off my clothes, wash everything out roughly – with moderate success. But never mind. First we all squeeze into the hot sauna, laugh our heads off at this mishap (which I’m sure happens quite often) and enjoy the heat followed by a tingling dip in the ice-cold ocean. Later, I am forced to make my way back in my underpants, wellies and my half-spared sailing jacket, this time preferring to take a detour via the rocky part of the colony. A thorough wash follows at the station: I jump in the shower, the clothes go in the washing machine, we go to the bar. Later, when we take the dinghy home to the Selma, our clothes are clean again and smell of Ariel instead of penguin.

Farewell

The next morning it’s time to say goodbye. We want to move on, our course points north. Ivan will stay here for another four weeks before the crew changes in April and, like most of the station members, he will be heading home.

It is an emotional, somewhat wistful farewell. We are all standing on deck as the Selma passes the station, the small wooden pier on which Ivan is standing and waving to us, and a few quick farewells are shouted back and forth. I’m very touched at this moment and my eyes are actually wet. Although we were only anchored here twice for two days each time, it was like leaving good, very close friends behind. During those days, Vernadsky was like a little home to us, a place where we were warmly welcomed and cared for. A place where we were protected and safe while two storms passed through outside. A place where we were able to get to know very special people at a very special time. It is hard to leave them behind, as we all face an uncertain future, but especially they and their families face a difficult one. Our thoughts are with them, even though we are now parting ways again. We are very grateful that they have crossed paths. Thank you Vernadsky!