What do you actually do at night?

We have often been asked this question.

The answer is the same as to almost all questions that arise here on board and in life in general: “It depends”.

No two nights are the same. There are quiet and restless nights. Quiet ones, loud ones. Silent, dark, gloomy. Comfortable and extremely uncomfortable. Nights in which we lie at anchor – whether at the bottom of the sea or on an iceberg – or drift at a tilt. And there are others when we are out and about.

What all nights have in common: at night, the Selma becomes a red light district. All white light is extinguished, leaving only a few dimmed red lamps to bathe the saloon and galley in warm red light. All instruments and the headlamps of those on or below deck are illuminated in red. Red because it doesn’t dazzle. Because it lets the night be night. Because we need to be able to see at night despite the darkness, to perceive our surroundings, to recognize ice in time and to avoid icebergs. The human eye takes a long time to adapt to the darkness, to get used to it. When it does, we can see surprisingly well, even if only dimly. However, a single bright ray of light destroys this adaptation and makes the sighted person night-blind again for quite a while. And of course it is also more pleasant for those sleeping when it is dark.

However, it never happens that everyone on board is asleep.

The watch system is also in place at night – whether underway or at anchor. Because you never know what will happen. Conditions can change quickly.

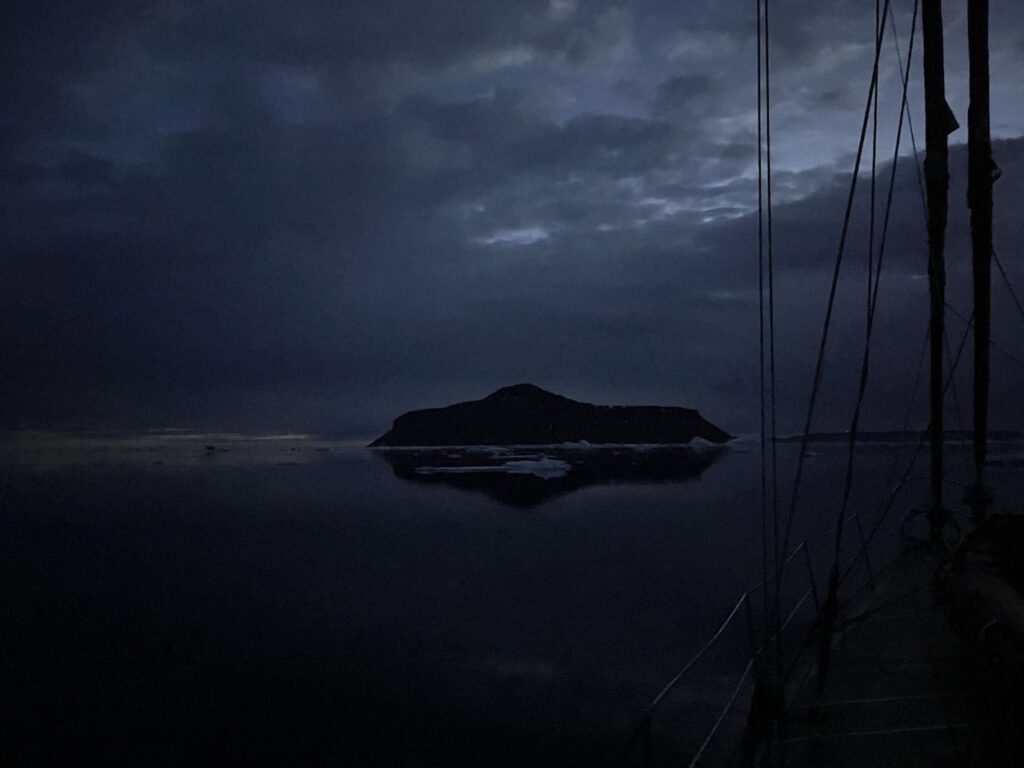

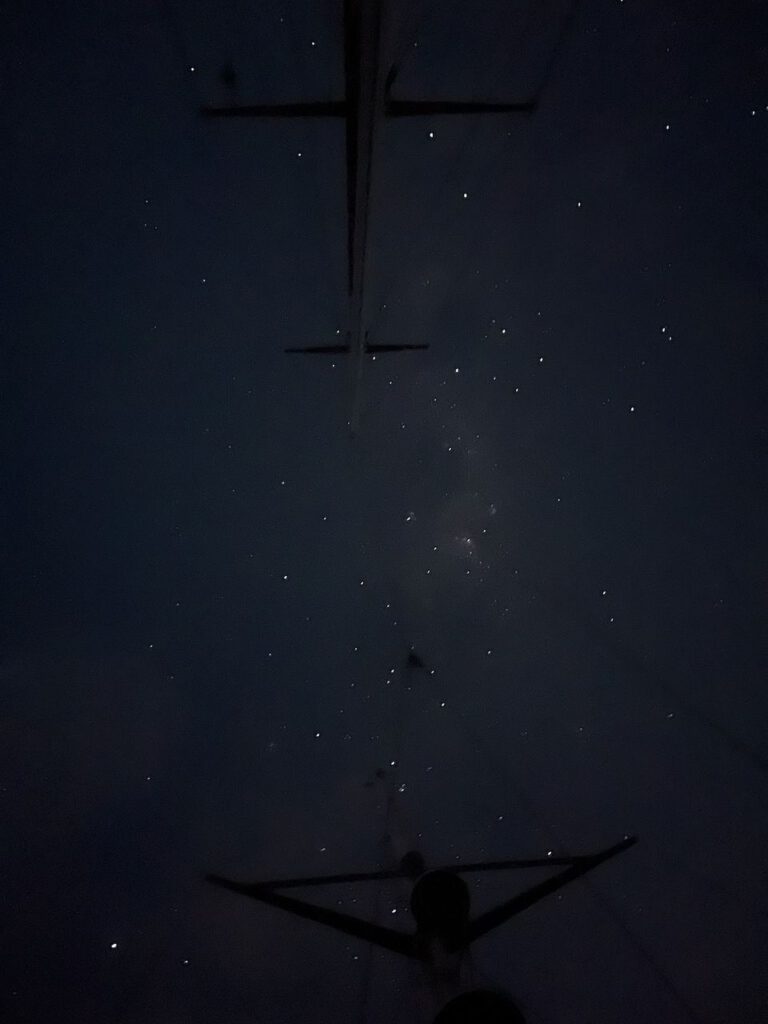

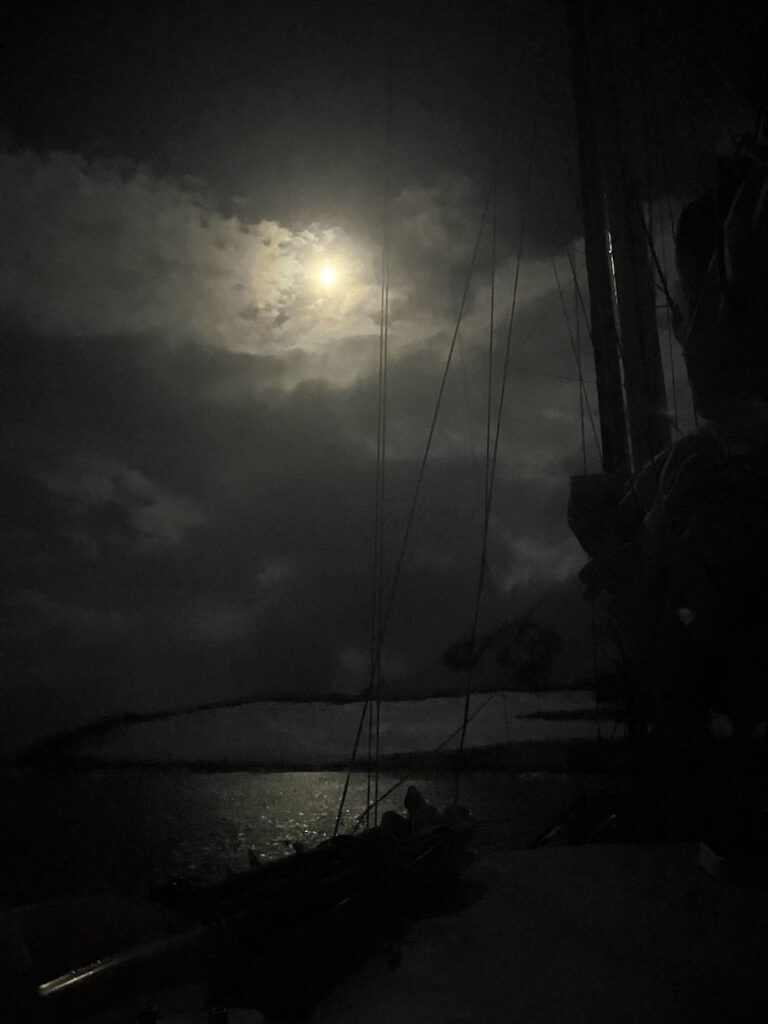

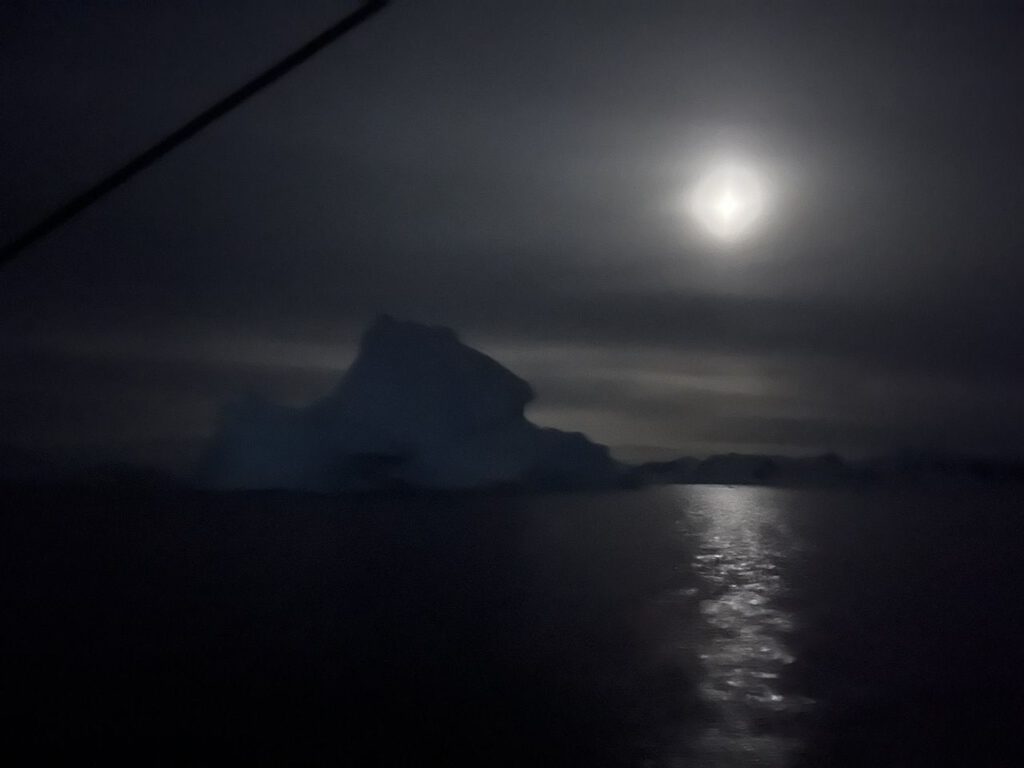

Lying at anchor or drifting alongside, at least one person keeps an anchor watch, watching over the Selma and the sleep of the others. Keeping an eye on the anchor, watching the ice all around. Sometimes these are wonderfully quiet hours, alone with the world. The water gurgles along the side of the ship, the soft crackling of the ice can be heard or a glacier cracks somewhere. Sometimes you hear the blow of a whale or the steady call of a neighboring penguin colony. The wind sings in the shrouds, the masts of the Selma sway under the starry sky, the familiar Orion lies close to the horizon, the Southern Cross crowns the firmament, now and again the moon can be seen and bathes the sea, ice and glacier in a silvery light. Some enjoy sitting alone on deck, wrapped up warmly, letting their thoughts wander or processing the day’s experiences and listening to the night. Others warm up in the wheelhouse or sit below in the saloon, using the quiet hours to read or write, only coming on deck now and again for a check-up. The night holds magical moments in store: when a circular halo appears around the moon, when the puffing breath of a sleeping whale can be heard close by or when you are lucky enough to watch the new day wake up, when the first dawn first wraps itself in a delicate pastel and later turns into glowing, flowing gold.

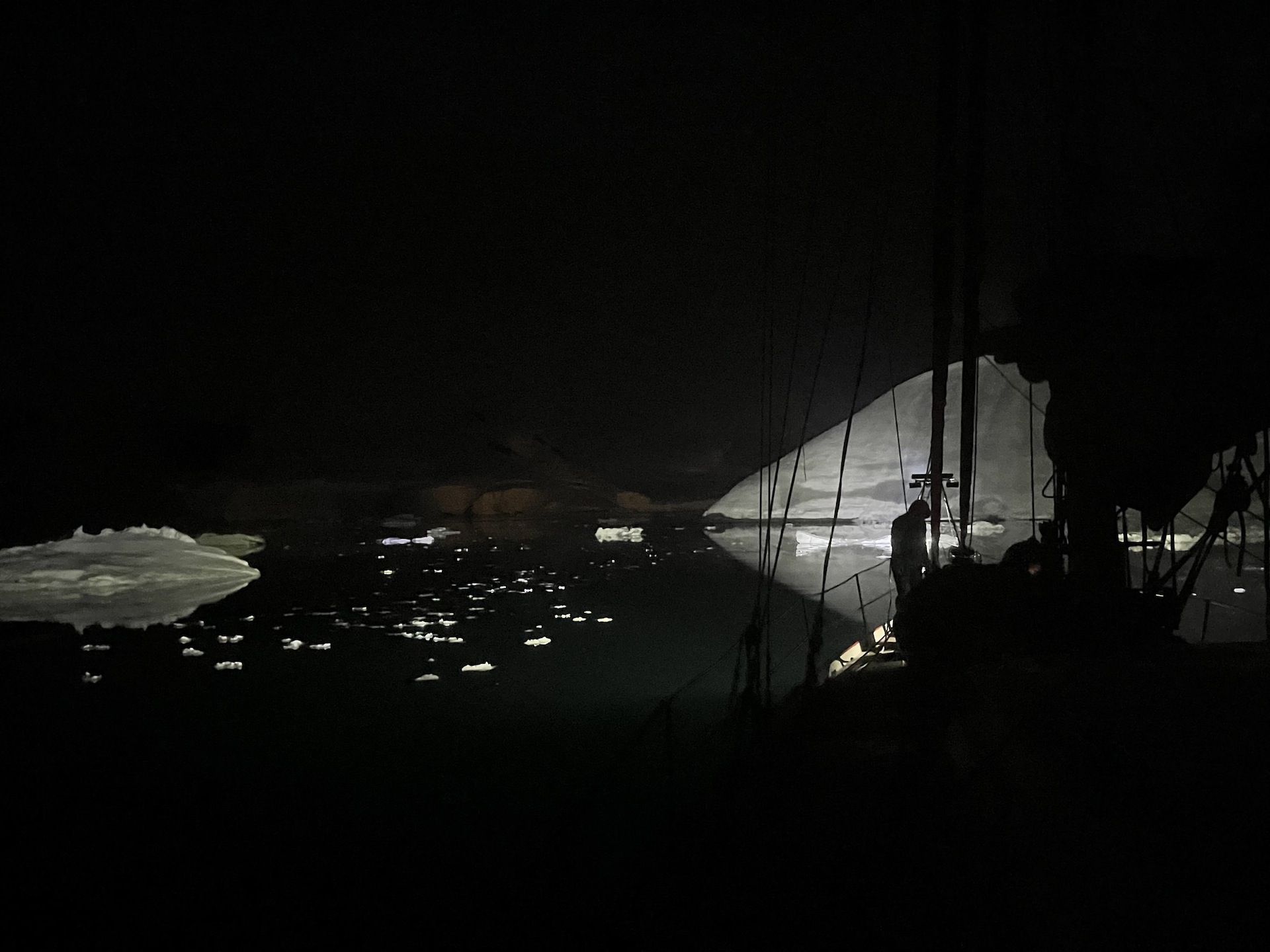

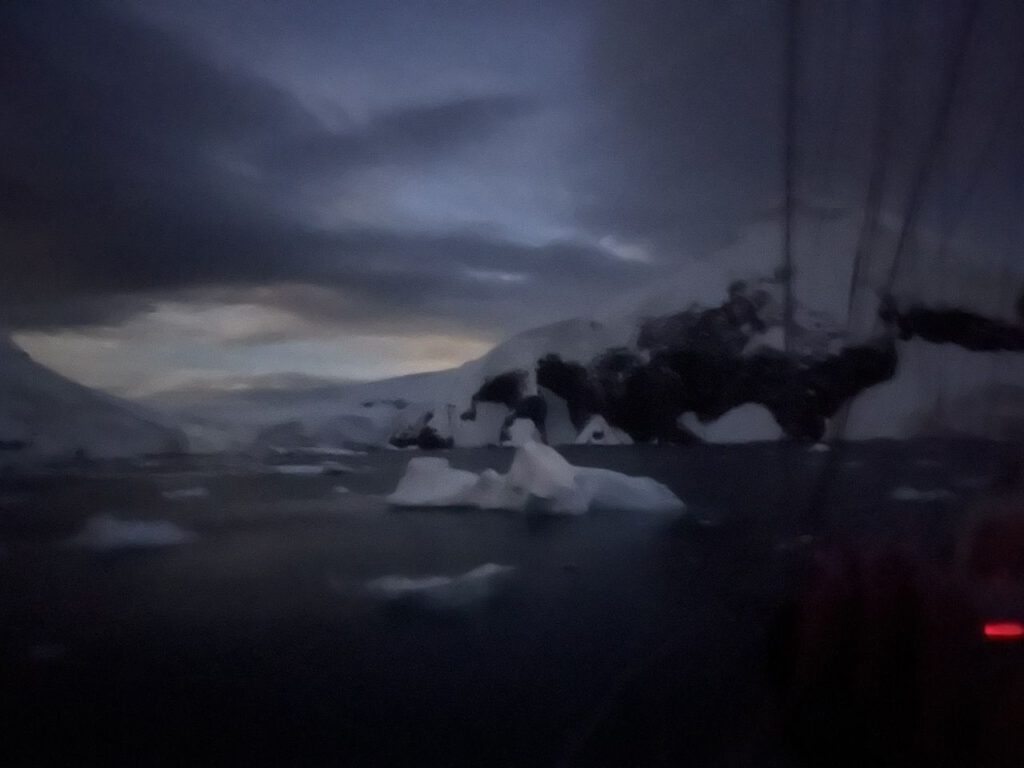

But the night can also be exhausting. When we are not so well protected, the wind and waves pull and jerk the anchor chain, the Selma rolls in the swell, everything creaks and groans, the anchor alarm goes off again and again. When the ice pushes into our bay due to current, wind and tide or drifts towards Selma. Then we have to prevent collisions. Sprinting across the deck with the long pole, from left to right and front to back … putting the ice floes, growlers and smaller icebergs (bergy bits) in their place and pushing them past the Selma. As soon as possible, so that they don’t scrape along the side of the boat, block the anchor chain or damage the rudder. This requires strength and can be quite strenuous. The ice has its own dynamics, the currents are strong and sometimes changeable. It’s not uncommon for the entire sweep of ice that you’ve just steered past from the bow towards the stern to drift back in that direction after a while, and the game starts all over again. In the case of larger icebergs that can no longer be moved by muscle power, the skipper is briefly woken up, the engine is started and with the help of Mr. Perkins, the boat is evaded or space is created. Piotr sleeps in the wheelhouse and is ready for action in a matter of moments in the event of an emergency. If the anchor pulls out, it has to be hauled in and set again – but fortunately that hasn’t happened yet. We have only had to set it a second time once.

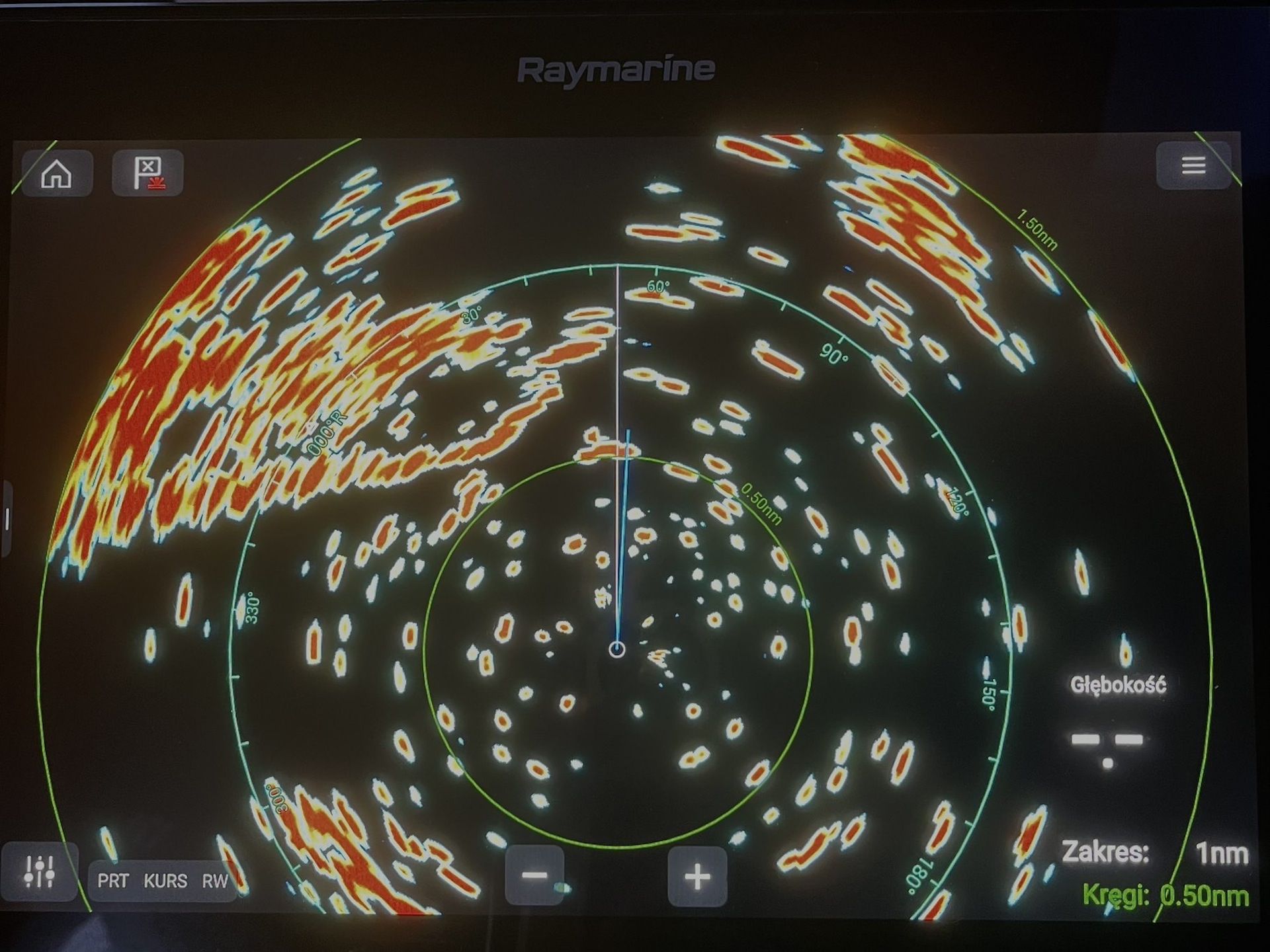

On other nights we are underway. We are still looking for a sheltered anchorage or sailing or motoring through the night – depending on the wind and ice. Two of us share a four-hour watch. One of us takes turns at the helm, the other stares into the darkness, always keeping a watchful eye out for ice. Or on the radar if the darkness becomes impenetrable, the weather too desolate or the ice too thick. Then it helps to see if a gap opens up somewhere on the radar screen. Sometimes there is no way through, the barrier is too thick. And we have to turn around and look for another way or make a turn. Then someone stands at the bow, points the way or clears the way with a pole. In this way, we have often felt our way through ice and darkness, carefully and with concentration. Sometimes supported by the light of a powerful lamp or the lights installed on the bow in the meantime (the only white light permitted). And so far we have always found a way.

And in between, there is always a good and caring soul who looks after the well-being and energy levels of those on watch. Who brings a second, dry pair of gloves, makes hot tea or coffee. Pushing a piece of chocolate into someone’s mouth or bringing a cookie. And there’s Piotr, who stands in the red light of the galley in the middle of the night and cheerfully whips up delicious gratinated toast in the pan. So you get through even the longest, coldest and most exhausting night watch, hand over the helm to the next person who is ready on time and then climb into your bunk, exhausted and tired, but satisfied and happy. And for a few hours at least, he does what most people do at night: sleep and – sometimes – dream.