We were blessed with numerous animal encounters that will remain unforgettable.

The albatrosses and petrels of the Drake Passage were followed by the penguins. These also deserve a chapter of their own. I wouldn’t have thought it possible – at least for me – but you fall head over heels in love with these creatures straight away. With their unintentionally comical nature, their curiosity, their sometimes clumsy movements on land and their swiftness in the water. We met Adelie, Gentoo and Chinstrap penguins and were lucky enough to spend time in their colonies, observing them in peace. You can do this for hours – it never gets boring. Their communication, their group dynamics, hungry chicks rushing after their annoyed parents. We found them out at sea, swimming like torpedoes, shooting out of the water again and again, drifting past in groups or sometimes all alone on an ice floe. We also saw two young emperor penguins, the colony was unfortunately denied us.

We often encountered skuas, skuas that prefer to stay close to colonies for their prey (penguin chicks). For their part, they vehemently defend their own chicks and clearly signal intruders like us, who accidentally get too close to the nests on the ground, to retreat by shouting loudly and flying towards them.

We met seals of all kinds, sometimes swimming elegantly in the water, more often lying lazily on an ice floe and dozing or on land. As Antarctic beginners, we almost stumbled over numerous fur seals sleeping on the beach (we now have a trained eye for what is a harmless rock and what is a sleeping seal). We spotted a pair of sleeping elephant seals cuddling and looked into the round, huge, black saucer eyes of the Weddell seals, which sometimes look bored, sometimes curious to see who is coming, raise their heads briefly, but then immediately calmly scratch themselves again somewhere with their flipper.

And we met the king of the Antarctic food chain (alongside the orcas): the leopard seal. Tall, slender, streamlined, often lying solo on the ice, they actually look friendly with their smiling faces. In the water, however, they become merciless hunters and are not exactly squeamish about their favorite food, penguins. The penguins are grabbed by the feet and then whirled around and around and hit the surface of the water (or even an iceberg) until they are de-balled (featherless) and ready to be eaten. It was a really impressive spectacle.

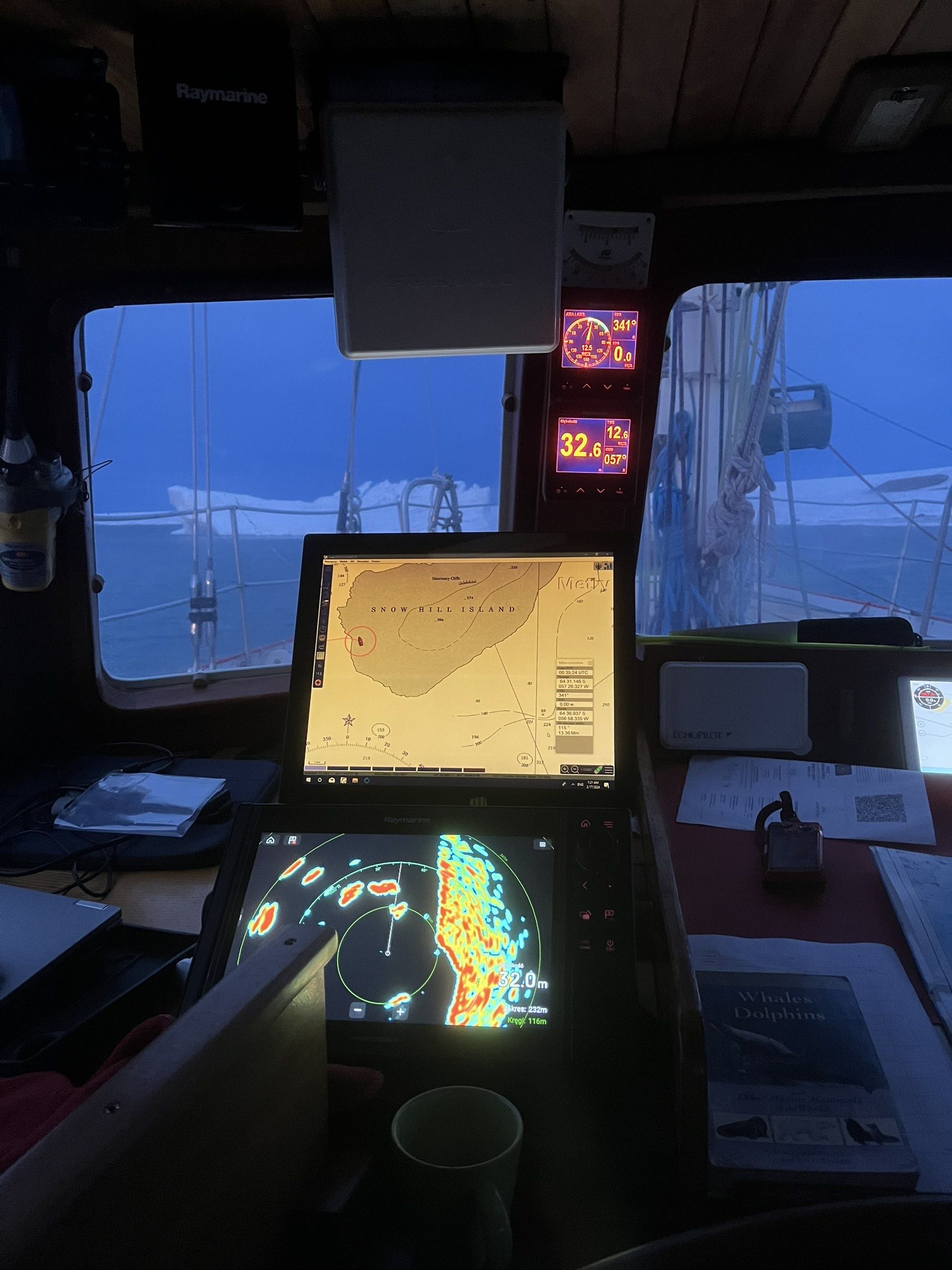

And of course we met whales! Usually announced by a loud cry of “Whale!” from the helmsman at the wheel. And anyone who wasn’t already on deck quickly crawled out of the wheelhouse or the saloon. The whales passed us by, sometimes in the distance, sometimes very close to the boat. Sometimes alone, often in pairs or in small groups of three to four animals. Most of them were humpback whales. It’s beautiful how they move gently and calmly through the water, wonderful to see their flukes as they dive down. But it was much more impressive to hear the sounds they make, the puffing as they blow, the whistling as they breathe. Loud and powerful. Especially when they were traveling in groups. Goosebumps and awe. This was also the case with the encounters with orcas. Out and about in groups, at first often only the huge sword of the fins to be seen, then up close the shiny gray bodies ploughing elegantly through the water. At these moments, it was completely silent on deck, everyone stared spellbound at the water and only the exhalations of the animals could be heard. No one moved or left the spectacle until the last fin had submerged again.

The local animal world is diverse and beautiful. And we have also seen the basis of all this rich life: krill. When they swarm through the water, the surface ripples a little, as if the sea were boiling. Bubbling and full of life.

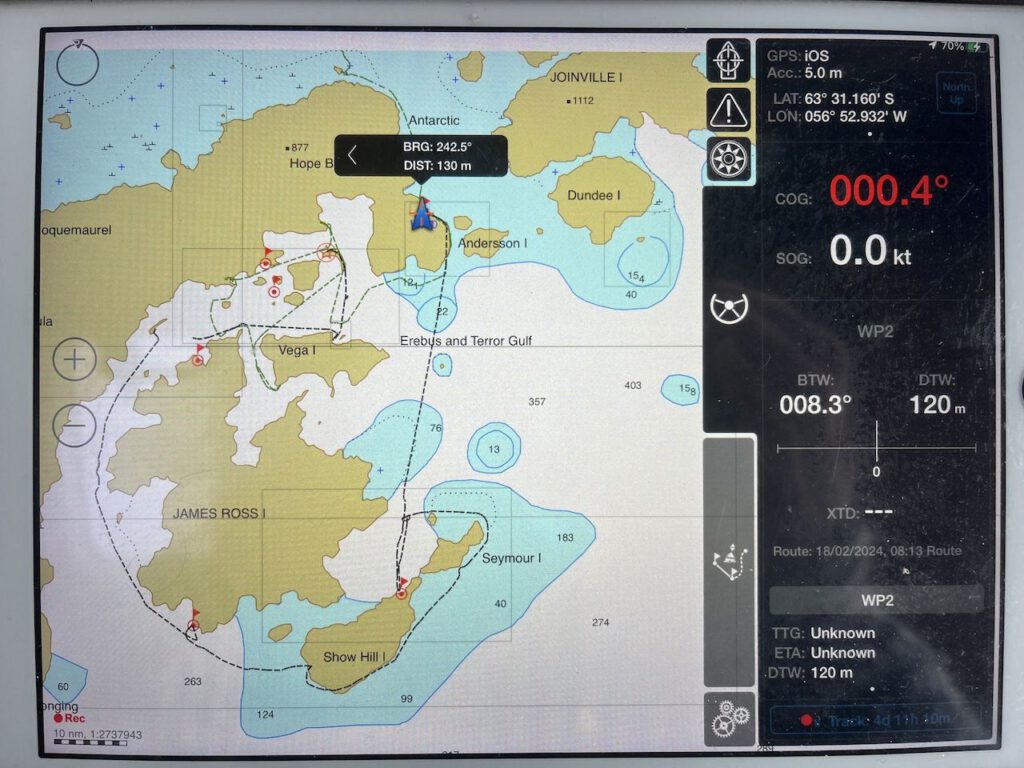

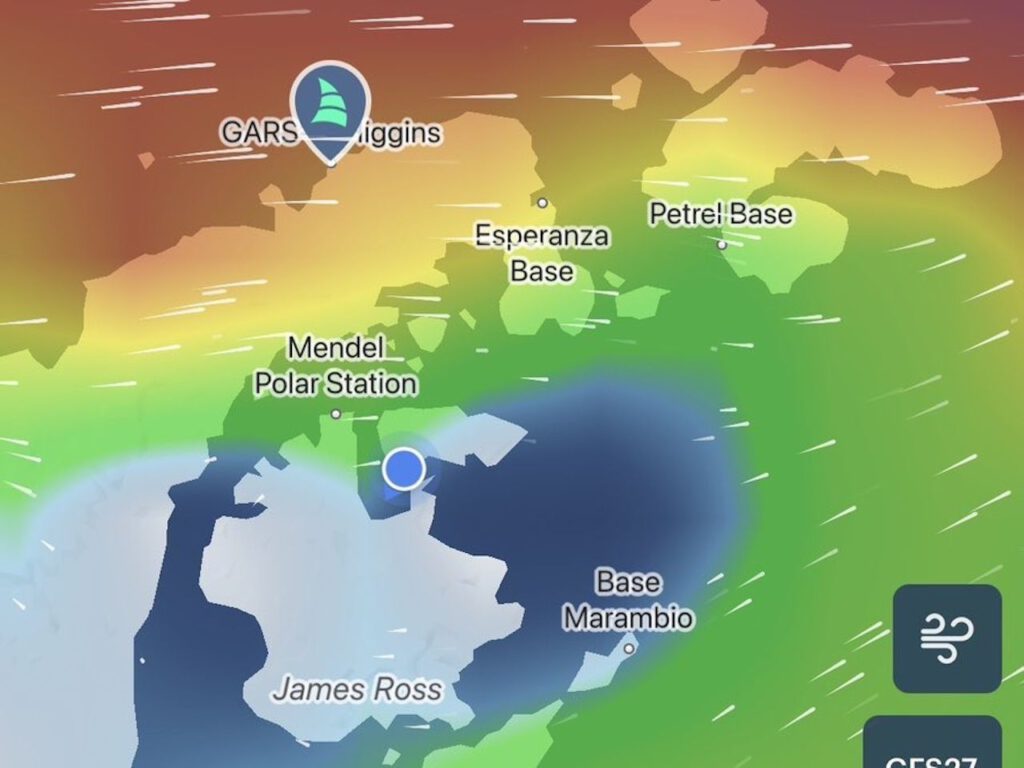

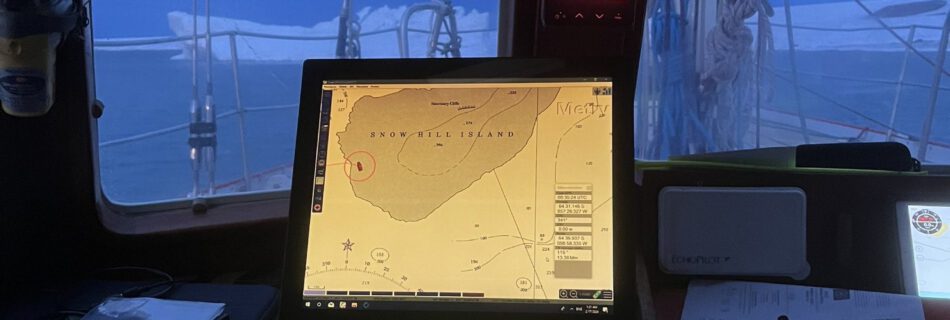

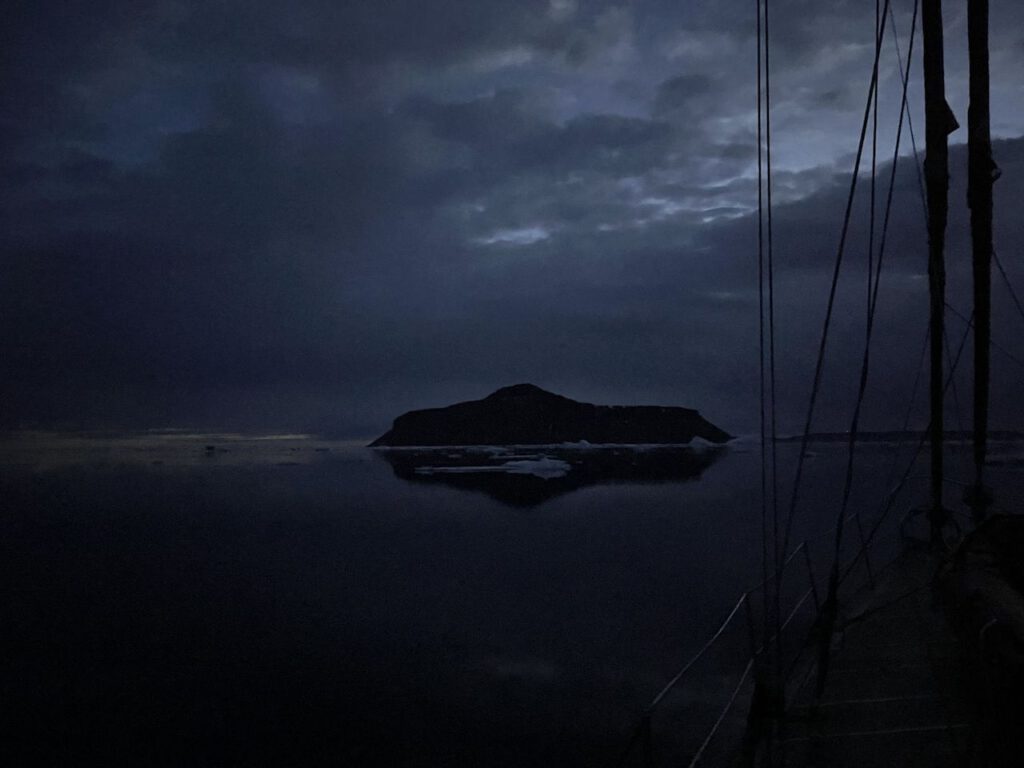

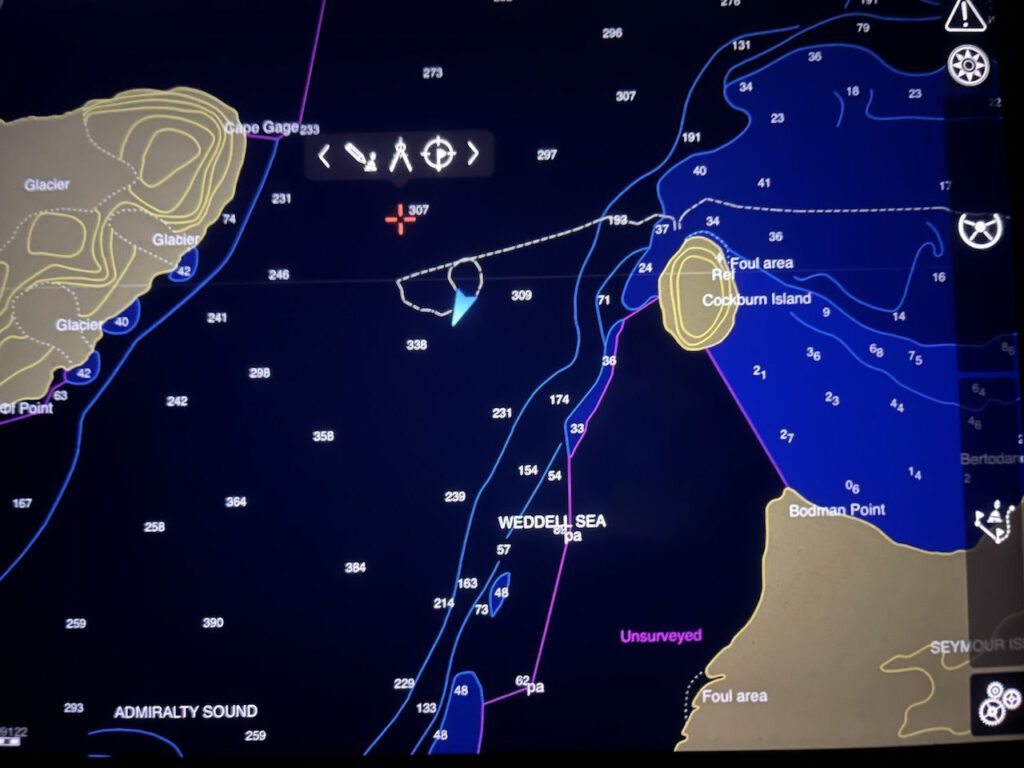

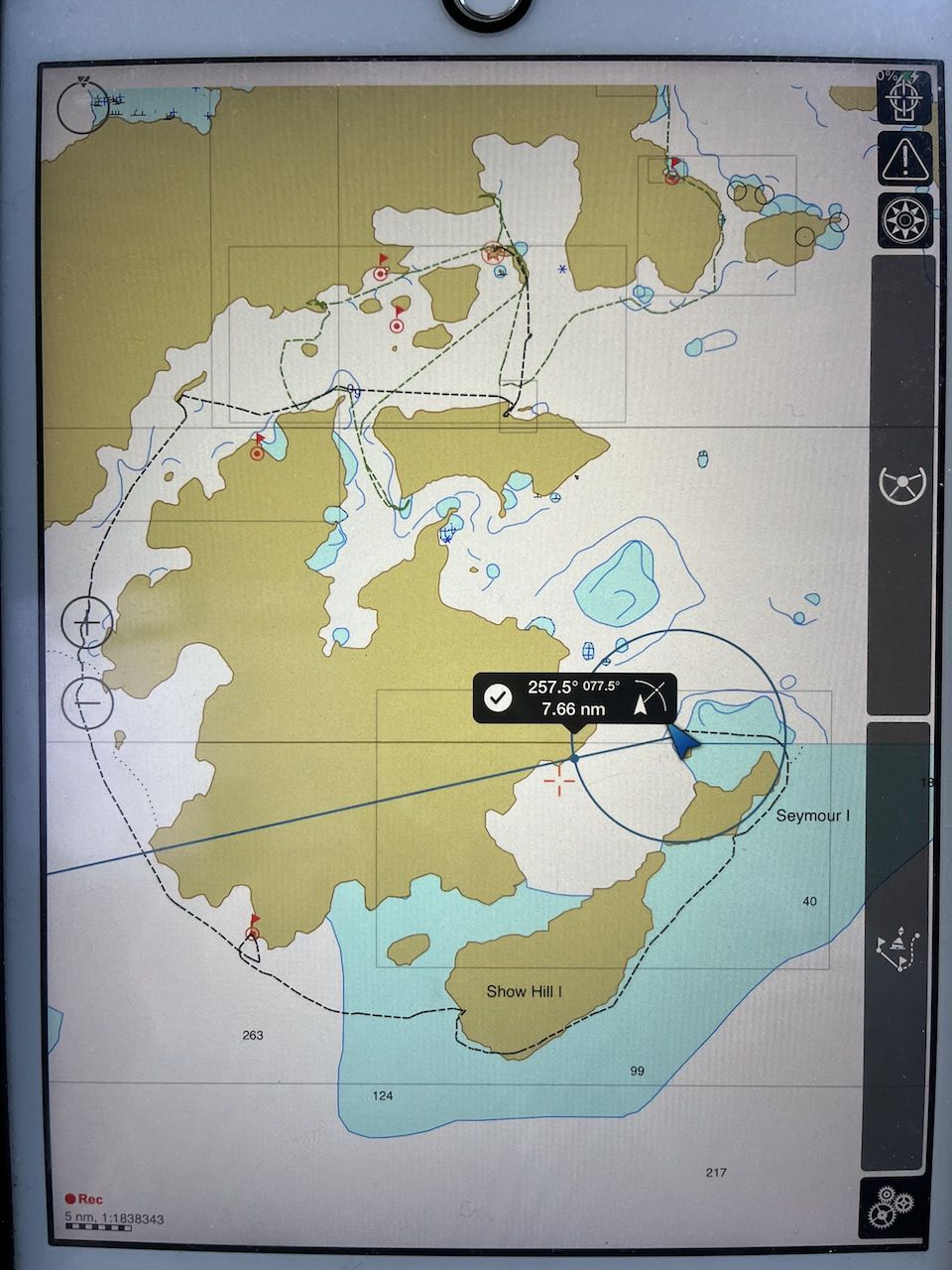

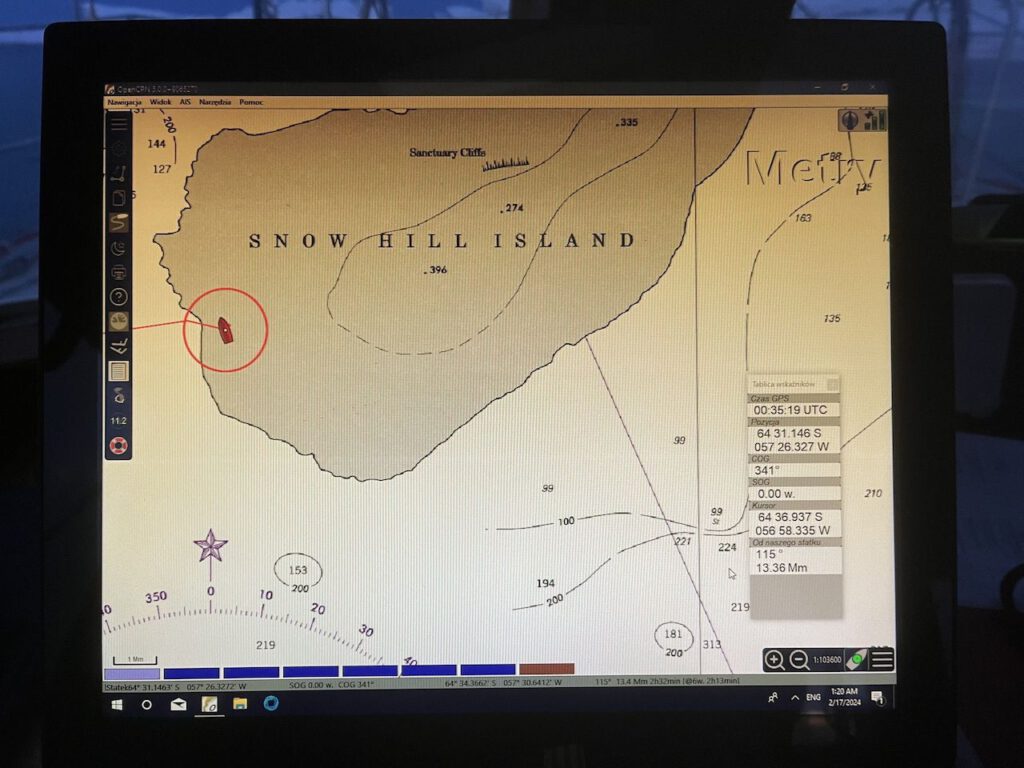

And so the circle closes. Just as our circumnavigation of the Weddell Sea has come full circle.

We are grateful to have been able to experience this. Now we are ready for the other side of the Antarctic Peninsula, where – at least in part – a whole new world, a completely different side of Antarctica awaits us.